These

days most people don't believe in miracles. I didn't either

until I witnessed one this past summer. It happened in Northern

Laos. Laos, is a land-locked country north of Thailand and west

of Vietnam in Southeast Asia. It is nearly the size of England

but has only about five million people (versus England's 60

million). It is a very pretty mountainous country with wild

rivers and deep forests. It also has the distinction of being

the country with the highest ratio of bombs dropped per person

of any place on earth. From 1964 to 1973 the US, in 580,344

bombing runs, dropped just over two million tons of bombs on

Laos. The idea was to stop the flow of guns and men along the

Ho Chi Minh trail from Hanoi to South Vietnam. "Collateral

damage" and "civilian casualties"--like we heard

about in the Kosovo war, was not a consideration. Everything

and everyone in Northern Laos was a target. To us the Lao people

were not quite human.

Even now no one knows how many

people were killed or the real extent of the damage, but everyone

I talked to had lost a family member in the bombing and certainly

every substantial building was destroyed. With that many bombs

dropped it's only natural that some did not explode. The US

military claims that 10% of the bombs didn't go off; other people

think that 30% of the bombs didn’t explode. But it doesn't

really matter what the numbers are: no matter how you figure

them, there are an incredible number of bombs that are waiting

for a woman gathering firewood to nudge, a farmer to strike

with his hoe, or for a child to play catch with if they are

one of the millions of baseball-shaped anti-personnel bombs

that were dropped.

In 1994 an international organization,

the England-based Mines Advisory Group, began a program to find

and explode those unexploded

bombs, what they call UXO (Unexploded Ordnance).

Last summer they asked me to help them design a database that

would keep track of how many bombs they had found and destroyed.

The 186 fields in the database formed a list of seemingly every

thing that could possibly fall from the sky. The US military

even dumped the bombs they had stockpiled from World War II.

These days the Mines Advisory Group,

or MAG, has a staff of 200 who have three basic tasks: (1) to

teach people what to do when they find a bomb, (2) to clear

(de-bomb) land where someone wants to build something and (3)

to explode bombs that people have found.

The educational component lectures,

passes out "Just say No to Bombs" T-shirts, and put

up posters to warn people not to pick up unexploded ordinance.

Earlier this year they went to a village and passed out the

T-shirts to a group of smiling children. The next day, by chance,

those same children spotted a bomb on the way home from school.

Most of the kids immediately got away from it. One boy, however,

the boy who had, ironically, sat in the front row of the bomb-awareness

class, started to play catch with the baseball-shaped bomb.

He shortly blew himself up.

Whenever someone wants to build

a building, a soccer field or make a road, they will contact

the Mines Advisory Group to come and de-bomb it. And they almost

always find bombs. A friend was staying in a guesthouse when

MAG stopped by. They found a bomb buried outside his window.

When I rode in from the airport they were working on a bomb

that someone had spotted in the ditch along the road. Once they

cleared the ground for a new school and found only three bombs.

Then the land was landscaped with truckloads of topsoil--those

truckloads contained, to everyone's horror, 35 baseball-sized

bombs. It's amazing. The clearance work is incredibly tedious.

First they survey the area and mark it off like the yard lines

of a football field. Next they, keeping a safe distance from

each other, sweep the yard lines with mine detectors. Every

bottle cap, nail, and old beer can has to be considered a live

bomb until someone proves it otherwise. The de-bombers work

in the cold rain, the hot sun, and the dirty mud, all for one

hundred dollars a month.

Education and clearance are the

boring parts of the job. The fun part is blowing stuff up that

people have found. The process begins with a MAG representative

visiting a village and asking the headman (mayor) to make a

list of the bombs that people have found. Often this is the

first contact that villages have with MAG. After the representative

checks that the bombs are actually there, he sends in a clearance

team. I went out with a clearance team one morning and watched

the woman in the above picture, Miss Lai, demonstrate her expertise.

She was one of seven people, excluding

the medic, on the team. As soon as we arrived at the site the

four sentries took off with bullhorns and walkie-talkies to

clear the area of people while the technicians strung a few

hundred meters of detonator cable from the top of a nearby hill

through the valley where a farmer had marked four bombs in his

lush pasture. As they strung the cable, they studied the ground

for even more bombs, but didn't find any. When the cable was

beside all four bombs, the team leader used his walkie-talkie

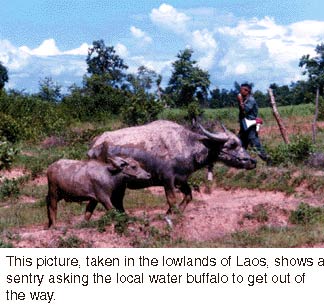

to checked in with his sentries. One

of them was hearding water buffalo out of danger, others had

told the people in near-by houses to leave. After a few minutes

they gave him the go-ahead. Miss Lai then put on protective

glasses, but no other protective clothing, and inserted a detonator

pin into a cigarette pack-sized block of TNT that the Mines

Advisory Group had bought from the Russian military "at

a very reasonable price." She then did the same thing to

the other three bombs.

It was raining and cold. I had

an umbrella; the demolition experts and the sentries had nothing.

(In Asia they've never stopped planting rice just because it's

raining--everyone somehow endures it even though they get as

cold and sick as we do.)

When the TNT was safely in place

we walked to the top of the hill from where we could see the

entire valley. The team

leader then want back to his walkie-talkie-the sentries said

that everything looked okay.

As the guest of honor, I was given the task of pressing the

button that would set of the TNT. I turned a crank that generated

a charge and when a light flashed I pressed the button. Ka-boom!

Four white puffs of smoke instantly dotted the valley. We then

did a check to make sure that the TNT had actually exploded

the bombs and not just pushed them away. It had--where the bombs

had been there was now a little crater.

To the Lao technicians and sentries

it was just another day. To me it was the most exciting thing

since the movie Armageddon staring Bruce Willis as Harry

Stamper. What, I thought, could be more fun than blowing up

old bombs?

Now let me tell you about the miracle

I saw. They don't hate us. No one I met hates us. I met soldiers

who had practically lived underground for years to escape the

bombing, people who had lived in the jungle, a woman who had,

when she was ten-years-old, walked for two weeks to reach relative

safely in Vietnam after the bombing killed her grandparents.

And no one hates us. There is a cave there where 300 people

were incinerated when it got bombed and still everyone I met

was warm and friendly. The Buddha taught that hatred does not

stop hatred, only love does. It seems to be a lesson that the

people of Northern Laos have learned very well. It’s a

miracle and something to think about at Christmas.

A few pictures

from Laos

(All pictures

were taken with my camera.)

The chief technicians in MAG Laos

are all former British Royal Engineers (munitions experts) and

are as tough as they come: Jerry on the left occasionally finds

a style of bomb that he hasn't seen before. When I was there

he brought one back to the office and took it apart. On the

day this picture was taken, in late August, he had woken up

with malaria. That’s me in the middle. Earlier this year

Peter, on the right, caught on fire when a phosphorus bomb he

thought had been detonated exploded. Phosphorous ignites when

it comes into contact with oxygen. Quick-thinking Peter took

off his clothes and covered himself in mud until he could reach

a hospital.