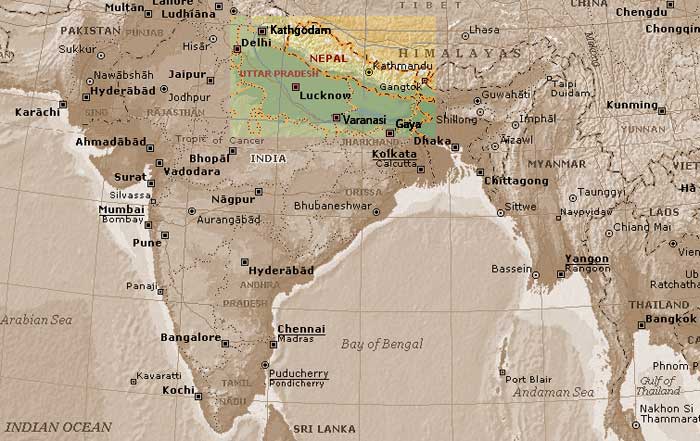

I am honored that the University of Delhi chose to publish part of this story in one of their textbooks. Travel Writing in India: Meditation and Life in Bodh Gaya, Sarnath, Varanasi, and Kathgodam.

by Tom Riddle, 2010, afterword 2022

Early March 2010,

touristing in Sarnath, India, just down the road from VaranasiAs I begin writing this travel log, I want you to know that for the last year I have had my own apartment back in Bangkok. This means that when I leave Thailand I no longer have to put everything in boxes that I hide in someone's closet. These days I just close the door and go. That's really nice.

A few years ago, for a while, I had a very nice apartment in Bangkok that I moved into after returning from a well-paid movie-making job. That apartment cost me 25,000 bhat a month, about $600. It was nice—there was a swimming pool down the stairs, a small kitchen, a living room, and a bedroom. When I left that apartment, I kind of didn't live anywhere for a while but then last year I started renting another apartment not for 25,000 a month but rather 18,000 bhat (about $500), a year. Considering the cost though, it isn't too bad. I have a room on the third floor of a shophouse, what Americans might call “a brownstone.”

On the floor below me live a Burmese couple and their 5-year-old daughter. On the ground floor the Burmese wife runs a small garment factory while her husband manages a nearby warehouse for a Bangkok publisher. On the floor above me lives a Canadian man, Victor, his girlfriend, Miss Wow, and their dog, Tasco, who never leaves the apartment. Everyone is happy to live there.

Now that I"m in India, I realize that my life in Thailand is one of luxury, ease, convenience, and cleanliness. In Thailand both the electricity and water supply are so reliable that no one I know has an auxiliary generator or collects rainwater. Additionally, the air inside and outside my building is not particularly dirty, and, because this is in the suburbs, the birds are the noisiest part of the morning. There are no cows, horses, or goats in the neighborhood although a few people keep chickens.

Yes, thinking about it from here in Sarnath, I now understand that everyone's life in Bangkok is one of incredible luxury, ease, cleanliness, convenience, sophistication, and wealth. No one thinks it's normal to have a constant cough or a life-long intestinal problem. Additionally, I've never known anyone to defecate or build a campfire in the streets of my Bangkok neighborhood. As far as I know, no one in Bangkok cooks with cow dung, almost everyone can read and write, and everyone knows how to use a flush toilet. If that isn't enough, everyone knows that Michael Jackson is dead. How sophisticated can you get? It's incredible. Down the street from where I live in Bangkok is a supermarket with everything in the world, the taxis are all air-conditioned, and basically the trains and everything else run on time. Is that paradise or what?

But I'm getting ahead of myself and the story.

Before I go on, I should say something about myself. I'm one of these American ex-pat types who has spent most of his adult life, overseas. At 51 I've been an English teacher, a refugee camp worker, a computer science teacher, and for the last ten years a movie maker. Making movies is great fun. Usually I make movies for non-governmental organizations about their projects. But now I'm on vacation.

On with the show . . .

Click any of the pictures that I've taken to enlarge them. Use your back arrow to return to the story. Step one in coming to India was taking a taxi to the airport. Every taxi in Bangkok is a Toyota Corolla, a fact that has made the man in charge of importing Toyota Corolla's to Thailand fabulously wealthy and equalized the city's taxis, none of which can be more than nine years old. When I left my neighborhood to go to the airport, my taxi carried a totem animal to give luck to the driver, the normal citizenry of Bangkok, and, in my case, people going to India. This, I immediately realized, was so incredible, and unbelievable to most Thais, that I took a picture of the turtle.

With that I began my trip to India on January 25, 2010.

First journal entry: February 10, 2009, still alive after 16 days in India

Naturally, after so many trips to India, I'm always alert and watching out for danger, tricksters, hustlers, and everything else that can befall the naive and inexperienced traveler to this country of one billion people, where 53% of the women can not read or write, and 25% of the population lives below the poverty line.

So, always on guard, as I stepped off the plane from Bangkok and into one of the poorest states in India, Bihar, I immediately asked the man at customs how much a taxi into the village of Bodh Gaya would cost. “Four hundred rupees,” he told me. There were no buses and the six other people who had gotten off the plane with me were in a tour group; their van, they said, was waiting for them. Thus I realized that I would have to take a four-hundred-rupee taxi into the village.

A minute later, as the only passenger on the plane who wasn't with a tour group, I was approached by a middle-aged man from the airport's only travel agency who asked me if I wanted a taxi into town. “How much is it?” I asked even though I already knew the answer. The travel agent looked like he had slept in his clothes for a week and not washed his face in days.

“Five hundred rupees.”

“That guy told me it's four hundred.”

“Who? Which guy?”

I pointed to the sole customs man on duty.

“He knows nothing. He is not from this area. It's five hundred.”

“Okay,” I said, “it's five hundred.” Almost exactly ten dollars.

The travel agent then walked with me to just outside the airport building where five or six taxis were waiting. He chose one of them and gave the driver one hundred rupees, about two dollars and twenty cents.Stopping me in the lobby of the airport had just earned the travel agent, who no doubt had bribed someone to be allowed to operate from inside the airport, in less than a minute, twice as much as an Indian laborer, if he makes the minimum wage, earns in a day.

The driver looked suspiciously like someone I had seen before. “He looks like Osama Bin Laden,” I said to the travel agent.

“Don't worry,” the travel agent said, “This man is Hindu. You are okay.”

The taxi was the famous Indian Ambassador Sedan Car. The Ambassador was, in the days when India banned all imports, India's most popular car. These days, as more foreign-built cars appear on the roads, some nostalgia is developing for the old Ambassadors. For me though, it is hard to imagine a more poorly designed and poorly built vehicle. It is as if someone described what a car should look like to someone who had never seen one before and then that person had, with no previous building or engineering experience, built the Ambassador in his garage. I got in, almost knocking my head against the front window as I sat on what resembled a park bench with padding. Osama shut my door, which could only be shut from the outside. He then, with difficulty, started the engine, and off we went.

As soon as we left the airport, I was overwhelmed by the poverty that engulfs India's rural poor. People were huddled along the edge of their fields, tending a few crops or their miserable animals. A few dark and dirty shops stood clustered in run-down villages. Other villages didn't have any shops and looked medieval with their crude brick, mud walls, and thatch roofs. This has been a particularly dry year. Everything looked desperate, worn out, and parched. Yes, I reflected, the Green Revolution saved India from utter starvation and famine, but that's all it did.

On the road from the airport into the village of Bodh Gaya. Ten minutes into our fifteen-minute journey into Bodh Gaya, our car ran out of gas. “One moment,” Osama said, using what appeared to be the only two English words he knew. He then disappeared with an empty beer bottle. He reappeared a few minutes later with his beer bottle filled with petrol. After a few more minutes of careful engine maintenance, Osama was able to re-start the engine and we proceeded smoothly into Bodh Gaya.

Because this is where the Buddha became enlightened the theory is that Buddhist pilgrims should come to Bodh Gaya from all over the world. In fact though, at least at this time of year, the overwhelming majority of pilgrims come from just one place: Tibet. Thousands of Tibetans jammed the streets, restaurants, and temples to pray for world peace. “Why can't you pray at home?” I asked one of them.

“It's better to do it in this holy place. More power.”

“Whatever.”

I checked into a hotel that a friend had written me about, the Embassy Hotel. Rooms there were 800 rupees or 11 dollars a night. I didn't know if that was a good price or not, so I checked in and immediately left to survey the other hotels in the neighborhood. The hotel next to the Embassy wanted 400 rupees a night. I went back to the Embassy and told the man at the desk that I was seriously considering leaving that very day. “Up to you sir,” he said. “We charge a 40% early departure fee, but you can leave as you like.”

“Other places are cheaper and just as good.”

“Five hundred rupees a night and no lower.”

“What about hot water?” I asked.

“Hot water no problem, sir. Turn on the left faucet and wait ten minutes. If still there is no hot water, we can bring a bucket to your room.”

“Sounds fine.” I had decided to stay. The bathroom in the 400-rupees-a-night hotel hadn't been cleaned in years.

My bathroom, like the rest of the room, had a tile floor. The room itself had a broken air-conditioner and a broken TV that an irate guest had vandalized by removing every control and cutting the power cord. It also had two narrow wooden beds covered with four-inch foam mattresses, a tiny table, and a small bureau. With both beds, if I put my head on the pillow and stretched out on my back, my feet dangled off the far end; I am 5 feet, six inches (168 CM) tall. It was far too dusty outside to ever open the window, leaving whatever ventilation that would enter the room to come in from under the door. As always with Indian hotel rooms, before I unpacked my bag, I scrubbed the floor with the cloth that I carry for just that purpose. The cloth turned from white to dark gray.

Scenes around the main stupa in Bodh Gaya. The author is in the far lower right.

I had arrived just one day before the beginning of the famous “annual ten-day meditation retreat with Christopher Titmuss.” Its fame comes from the fact that Christopher has been teaching this retreat for 34 years. This would be the fourth of those retreats for me to attend, the first being in 1984. The retreats take place in a temple that the Thais built for Thai pilgrims. It's a beautiful temple with luxurious guest rooms for pilgrims. Unfortunately, though, Western pilgrims don't rate a Thai-pilgrim guest room. Instead, they are asked to stay in barren dorm rooms, on the open veranda, or under the main temple in what feels and looks like a dungeon. If you hung a few skeletons down there, they'd be right at home.

The Embassy Hotel, two views of the Thai Temple and Christopher Titmuss teaching. Rather than brave the dungeon, the tuberculin dorm rooms, or the freezing veranda, I decided to stay in the Embassy Hotel which, fortuitously, was just across the street from the Thai Temple.

About a hundred people used to attend the annual Christopher Titmuss retreat. But this year, with the world in economic crisis, terrorists in India, and the fact that India, tourists believe, is slowly melting down as the infrastructure collapses and the population increases, only about 60 people attended the retreat.

Everyone traveling in the 3rd world should have this book on their computer. Things proceeded smoothly. Because I've been to India so many times and lived to tell the tale, the retreat management decided that I would be the medical officer. This meant that while other people cleaned the toilets, swept the walks, or did odd jobs for thirty minutes in the morning, my job was to tend to the sick. This meant sitting beside a suitcase filled with medicine, reading Where There is No Doctor, and passing out advice and drugs.

I took the job seriously and under my care no one became seriously ill during the retreat. A lot of people, however, got diarrhea, colds, flu, constipation, and coughs. Plus one guy got scabies, probably after petting one of the temple dogs and not washing his hands.

Along with everyone else, I did everything I could to take care of myself. I was convinced that with yoga, vitamins, massive amounts of alcohol-based hand sanitizer, and by being extremely careful with my personal hygiene, I would be okay. I lasted a total of seven days at which time all of my hygiene, Western and Eastern medicines, and yoga were useless in the face of this year's Indian cold, flu, cough, and laryngitis viruses. But at least I didn't get diarrhea or scabies. I did, however, get some kind of stomach bug that produced intestinal gas that no human being should have to endure under any circumstances especially while on a silent meditation retreat and sleeping in a room with very little ventilation. That kind of intestinal gas would have shattered even the strongest of male/female bonds. What a relief it is, from time to time, to be living the life of a bachelor/monk.

Meanwhile, the Embassy Hotel went from bad to worse. On my second night there my room filled up with smoke as someone built a campfire outside and immediately below my third-story window. Then, on the third night, just as I was entering deep sleep, I felt a rat crawling on me. Yes, a genuine rattus. At that instant both the rat and I jumped out of bed. I turned on the light just in time to see the rat running under the door. Damn, I thought, the rat has come for my chocolate! I should have known that my delicious filled-with-antioxidants 85% Cocoa Dark Chocolate that I had carried from Bangkok would attract Indian rats. But what to do? I needed to think fast and hide the chocolate from the rat. I opened the bureau drawer to stash the chocolate and a second rat jumped out! Stay calm, I reminded myself, he didn't bite on the way out! But now what to do? I put my pants on and ran down three flights of stairs to the front desk.“There are rats in my room!” I shouted.

“No problem, sir,” the deskman said. “The rats are not living in your room, only visiting.”

He really said that.

“Only visiting? But the rats could bite me.”

“No sir, don't worry sir, the rats won't come back to bite you.” The deskman proceeded to give me, as if he had been keeping it beside him waiting for someone to ask for it, a towel to jam under the door of my room to prevent the rats from entering again. He didn't think that sleeping with rats was a major problem or anything to lose sleep over.

So I jammed the towel under the door, crawled under the two heavy wool blankets in the cold night air, and soon was fast asleep. Like all sentient beings, rats, if one can take a Buddhist view, are only doing what it takes to find happiness. Everything is passing. In the material world all attachment to things and wanting things to be any way other than the way they are only brings suffering and sleeplessness. At times like this the wise just close their eyes and drift off to sleep. Why worry? Besides, I was tired and the bed, after a day of meditation, was very comfortable.

The next day I told the story of the rats to the managers of the retreat. They were not impressed and indeed they all had rat stories of their own. One man, Christopher, had once become entangled with a rat under his mosquito net. Someone said that rats like to gnaw at people's heels because the skin there is so thick there that the rats can get quite a mouthful before the sleeping person wakes up. Rats, to paraphrase the deskman at the Embassy Hotel, are nothing to lose sleep over.

Fortunately for me, the towel trick worked and I never saw the rats again. Now, looking back, as far as I can tell, other than occasionally waking up in the middle of the night and wondering if there is a rat on my bed, I've had no long-term negative effects from my stay at the Embassy Hotel.

Until you actually do a ten-day silent Buddhist meditation retreat, it is pretty hard to know what it's like. It's different for everyone, but lots of people get all kinds of body aches and pains from sitting cross-legged six or more hours a day. Other people get restless, bored, and think that they are going crazy. Sometimes, when they can't stand the silence any longer, they go to the medical officer, in this case, me, and ask if they could have malaria, how long they should wait before treating diarrhea, or, they just make something up so that they can exercise their vocal cords for a few minutes and hypothetically verify that they aren't going insane.Fortunately for me, I've been doing retreats for so long that nothing surprising happens to me anymore. These days when I sit on a meditation retreat, I occasionally find a place of great peace and contentment, or, not finding that, I investigate what is stopping me from having great peace and contentment. On this retreat something that happened earlier in the year replayed in my mind again and again. At that time I had said something helpful and wise to an old friend, but that friend had taken it with great offense and anger, accusing me of questioning her sanity and recklessly trying to interfere in her personal life. (As if I gave two hoots about her personal life!) That movie played in my meditation-mind/brain again and again. The strange part was that every hour the movie had a different ending -- the person apologizing for her anger, me confronting her about her hair-trigger anger, more soap opera antagonism, me persuading her to try meditation, etc. Finally though, for some reason it occurred to me to take the advice of the Buddha and start to recollect some positive trait that person might possibly, if one looked closely enough, possess. It didn't take long to remember the tremendous kindness and generosity that she had always shown me. Then the mind quieted down.

That was a relief.

Breakfast on the retreat. The temple rickshaw driver. Vegetable market in Bodh Gaya. Traveling by motorized rickshaw in Bodh Gay. I can remember just one other thing that came up during the retreat. These days in Bodh Gaya, just as one enters the vegetable market, someone has placed a baby girl on the concrete in the hot sun with a small bowl nearby for passersby to place coins in. The child's legs have either been cut off or she was born without them. What to do? If one gives money, wouldn't that encourage more parents to cut off the legs of their children or to place children with deformities in the hot sun? Can a person just ignore her? It's something to think about. If nothing else, it puts the problems one might associate with a miscommunication, the common cold, intestinal gas, and visiting rats in a new light.

For the rest of the meditation retreat I tried to ignore the packs of skinny, barking, mange-filled-and-fighting temple dogs, the thickest mosquitoes I've ever seen, the smell of burning garbage, and the other retreatants, many of whom looked like they were not having much fun.

The retreat ended with everyone sitting in a circle and sharing their experiences of the retreat. To my surprise, even the people who had always looked like they were sleeping, bored, or going crazy said that it had been one of the great experiences of their lives and that they were incredibly grateful to the teachers and staff for everything.

So it goes. Often in life, I have noticed, things are not what they seem.

That afternoon, just after we finished cleaning up around the temple, Christopher Titmuss took everyone over to the school that he and other Western meditators started in the 1990s, the Pragya Vihar School. There the children put on a cultural performance. These days popular Indian culture consists mainly of over-sexed music videos and a type of over-sexed music that they call Banga. Well, guess what? The older children in the school presented us with a Bollywood-type over-sexed dance production. It was fantastic.

Kind of sexy, huh?

On the way to the school. Backstage at the cultural performance. To the right is one of the many street-based tailors.

I spent two more nights in Bodh Gaya. Everything went well. I found an Internet cafe that had wi-fi, something that didn't exist in Bodh Gaya during my last visit, three years ago. The cafe was the storage room in the basement of a hotel that had been radically repurposed. I came to like the place with its bare light bulb and dinginess. It was romantic as anything — like a room where James Bond is almost tortured to death before he makes a dash for the door and throws a hand-grenade back inside blowing everyone there to smithereens.And strangely, that's what happened, sort of, in another part of India. In Pune, in a cafe that tourists frequent, the German Bakery, someone placed a bomb that later exploded. It killed 17 people and injured 60. Last year terrorists killed 173 people just north of Pune, in Mumbai. As India and its neighboring countries deteriorate, more and more desperate people do more and more desperate things. One terrorist wrote that before he became a terrorist he was just another jerk on the street. After he started blowing people up, he got respect. Yeah, whatever. Meanwhile, mothers are crying their eyes out, and everywhere on earth people are dying in the name of religion and nationalism.

On the train to Varanasi. I'm writing all of this in Sarnath. Two days ago I made the six-hour train journey here from Bodh Gaya. The surprising thing about the train journey was that the train was on time. That is, it was only 45 minutes late which is the same as being on time in India. Friends had spent 12 hours on a tain platform in New Delhi waiting for their train to Gaya. Those same friends told me that if one wants any proof that India is dying, one doesn't have to leave the capital, New Delhi. About a thousand new cars enter the streets of New Delhi every day causing an almost constant traffic jam everywhere. When I was there three years ago, I clearly remember that the sun couldn't make it through the smog and pollution in such a way as to cause me to ever use my sunglasses.

I've spent days and days on Indian and Thai trains. I spend my time on Thai trains drinking beer and watching movies on my computer. I would never do that in India. In India, the custom is to tell whoever is sitting near you your entire life story. I know that that sounds strange, but that is what happens every time. This time my traveling companion was a recent university graduate who had come to India to find herself. I had met her on the Bodh Gaya retreat. As the train moved through the darkness and the smoggy Indian morning began, we revealed to each other our life histories. Now we know the intimate details of each other's families, our love lives, and how we've tried to solve our personal problems. Her main personal problem in India is that, thanks to the incredible deliciousness of Indian sweets like gulab jamun and burfi, she has developed an addiction to sugar and, equally horrifically, she confessed with an embarrassed smile, she is gaining weight. Gaining weight? To me she looked like Raquel Welch in the movie One Million Years B.C. I assured her that I knew a cure for sugar addiction, having once suffered from it myself, and that I would help her over the coming days.

She, like me, will stay here in Sarnath for ten days--enjoying this quiet small town that is, like Bodh Gaya, a place of Buddhist pilgrimage.

The parks in Sarnath contrain the remains of what was once an enormous center of Buddhist study and practice. It was here, in Sarnath, that the Buddha preached his first sermon after attaining enlightenment in Bodh Gaya. At that time after walking, 211 kilometers or 131 miles, from Bodh Gaya to Sarnath, he explained to his five old friends that, well, life had an element of suffering in it, but one could still, somehow, find an end to that suffering, and what we might call happiness and peace. Buddha would spend the remaining 45 years of his life explaining in greater detail and with more clarity than anyone had before or has since, how to find that ultimate contentment and how to end all suffering. He started his life's mission by telling his five old friends the Four Noble Truths and the Eightfold Path. At this time, I can't tell you any more about the Four Noble Truths and the Eightfold Path except to say that usually Westerners think that Buddhism is only about meditation. I'm here to tell you that the Buddha told people to follow eight steps to find ultimate peace and happiness. Meditation was involved only in the last two steps. The Buddha never said that any one step was any less important than any other step.

Two weeks later, February 24, alive in India for 30 days and still in Sarnath

Raquel Welch ended up staying in Sarnath for 12 days. On day one of her stay I revealed to her my cure for sugar addiction: simply eat fruit, as much as you can, as often as you want, for ten days. A fruit fast, I explained to her, would cleanse both the body and mind and give new insight into food, eating, and the nature of addiction. Everything I said sounded crazy to her, but the alternative, gaining weight and thinking about sweets all the time, didn't have much appeal either, so she tried it.The first three days were pretty rough for her. Then her energy level picked up along with some mental clarity and slowly she realized that she could actually live, and not die, while eating just fruit. After that her skin took on a healthy glow, and, according to her, by the end of her fast she had stopped having her usual sugar/food cravings and had a new level of energy. Sometimes things go well, better than expected.

After Bodh Gaya, quiet and peaceful Sarnath, with its relative lack of congestion, impressed everyone here as a kind of Shangri-la. Later though, some people, including me, thanks to the dusty, smoke-filled air, became sick again. They also started to get irritated by the various temples that make it their sacred duty to wake everyone up at 4 am with their low-fidelity, but very loud, Buddhist and Hindu chanting. That was on the quiet nights. On the non-quiet nights, because this is the wedding season, Buddhist and Hindu chanting were, by comparison, a calming relief from the non-stop ear-splitting Indian rap-rock-pop-Banga music that is played all night during weddings.This time, after I fell sick, I was convinced that I had either tuberculosis or a serious chest infection. I gave myself the benefit of the doubt and bought a bottle of codeine. The opiate in codeine helped me sleep, but it took away my brain. It was interesting. I would begin to meditate and, after watching my breathing for five breaths, I'd be, still sitting, sound asleep. When I would do this in a public place the meditation teachers and everyone else assumed that I had lost my mind. “Give me a break,” I told them when I heard my name being slandered, “I'm on drugs. I am living proof that drugs are bad. Don't you see? Drugs are bad!”

But I'm getting ahead of the story again.

Christopher and Jaya teaching in Sarnath.

Thanks again to Christopher Titmuss, there was a meditation retreat, of sorts, here in Sarnath. Christopher felt that if people were ever going to understand the basic ideas of Buddhism they needed not just to meditate, but to talk about Buddhism, especially how it fits into their daily lives. Does that make sense? So every morning and every afternoon for a week, sixty or so participants had discussions about things like “Living Simply,” “Generosity,” or even “Successful Relationships.” Because I was busy making movies, which I'll tell you about later, I could only go to a few of the groups and never knew what to say or how I might fit in. Every time I spoke I wondered if anyone could understand what I was saying.

One of the groups was about renunciation. No one there knew anything about renunciation. Someone said that they had to renounce their apartment before coming to India. Other people had recently renounced their boyfriend or girlfriend. Renunciation, I thought, goes something like this:The Buddha said that the natural state of the human mind is calm and clear. To reach that natural state he asked his followers to let go of or renounce, greed, hatred, and delusion. In meditation, that renunciation means standing back and just observing the daydreams, fantasies, planning, worries, and anger that arise in the mind. Get it? You're enlightened already, you just have to renounce, or refrain from, what is standing between you and complete awakening.

Who knows if anyone had any idea what I was talking about? I always feel like an idiot after opening my mouth in those groups.

There was, however, one especially nice thing about this non-retreat, retreat. The fact is that because this is Sarnath and not Bodh Gaya, where the chances of getting sick are about ninety percent, a few people, old friends from years past in India, stopped by just to say hello and to socialize a bit. Many of those people have done serious and intensive meditation for so long that they have found some kind of inner spaciousness that, is, well, wonderful to be around. I was glad to see them.

But, I was busy making movies. Christopher Titmuss, after talking about it for years, finally, decided that the two of us should put together an eight-minute slide show where he described the good parts of his 65 years of life. Starting in his late twenties, he had spent six years as a monk in Thailand and India before finding his true calling as a father and meditation teacher. He seems happy with the way things have gone. What more can you ask for? Check it out on Youtube.

After that I made movies for two other meditation teachers-- Jaya Ashmore and Gemma Polo.Jaya had somehow survived the Harvard Divinity School and was already teaching meditation when she met and fell in love with a beautiful Spanish woman. Gemma, who had some kind of spiritual insight as well. Now the two of them are married with a son (don't ask me anything about biology). They teach meditation in India, Europe, and the USA. They told me that they have a retreat center of some kind in Spain.

For two days Jaya, Gemma, and I talked about the fifty ways to make a movie before deciding that the easiest thing to do would be for them, one at a time, to simply walk down an Indian street and talk directly into my camera. To keep the camera from shaking I would be in a rolling dolly that would cost hundreds of dollars in the USA or Europe to rent for a day, but which we could rent for about one dollar in India. Our dolly was a bicycle rickshaw. It took us about a minute, with Jaya and Gemma speaking broken Hindi, to train the dolly operator. In their movies they say about the same things. The only difference is that Jaya is speaking in English and Gemma in Spanish.

Filming from our rolling dolly in Sarnath.

Because Sarnath is, in its own way, a center of the Buddhist world, someone set up an experimental school here. Actually, it has been an experimental school for so long that now it is no longer an experiment: it's a success, a proven formula. The school is “The Alice Project” referring to in Alice in Wonderland.

The idea was, I think, that just as Alice created a magic world in her mind, the students would create a calm world in their minds by using the teachings of the Buddha, mainly mindfulness, to help them with the problems of their young lives. So instead of telling the students to fight like a man, or just ignore the problems of life, which is what happened in my high school, they are urged to observe and be aware of what is going on in their minds but not necessarily to act on their anger, internal violence, greed, and hatred.

Besides the mindfulness training, and an apparent excellent academic record, the school is well managed and the spacious campus is designed like a garden. An Italian, (Italians are widely known for their design skills) Valentino, set up and runs the school. Four years ago I told a friend about The Alice Project. She came here, volunteered, took lots of pictures, and later, with my help, turned those pictures into a movie that Valentino saw and liked. Today Valentino remembered me and graciously offered me a cup of tea when we met at his school. (http://www.aliceproject.org).

According to Valentino, India is heading toward a disaster of world-shaking proportions. Here, he says, are 200 million people, the Indian middle class, who want everything, and don't care how they take it from the other 800 million people who live here, the rural poor. (Unlike in China, the rural Indian villages have not, by and large, benefited from urban development.) By using the Western development model, and not the Mahatma Gandhi development model, India, Valentino says, is quickly digging a deep grave that it won't be able to get out of. He says, "I tell my students that we shouldn't be teaching them math, science, and history because, first of all, those things will never get them a job, and second, because what India needs now is people skilled in disaster management."

Valentino and the Alice Project. Two hundred million people are traveling by car in India; 800 million are in the horse cart. Valentino has seen the land available for farming in this area shrink and at the same time the water table has become lower. Now he says, and I noticed this too, the Ganges River is lower and dirtier than it has ever been. If the mother of all rivers is dying, what is the future?

Scenes along the Ganges River in Varanasi. Things, Valentino believes, are bad and getting worse. Nevertheless, he says that he is happy as long as his students are happy. Fortunately, just today his upper-level students were having their farewell and good luck party, and I was invited to attend. I accepted. The graduation party consisted of perhaps 50 speeches and songs by the enthusiastic students who adore Valentino. When the speeches and songs were finally finished, everyone was treated to a traditional Indian lunch served on throw-away Styrofoam plates and washed down with Coca-Cola served in throw-away plastic cups. The evils of development were one thing, Valentino seemed to be saying, but who wants to wash the dishes?

Bhikkhu Gurudhammo and Tom Riddle, 1983 and 2010. Leaving the school, I walked up to Sarnath's Thai temple to see an old friend, an Indian monk who, over a three-year period during the early 1980s, spent many months with me in the same meditation center in Thailand, Vivek Asom. At that time he, Bhikkhu Gurudhammo, was a good-natured enthusiastic skinny young monk.

These days he isn't so skinny but he is still good-natured and sweet. As I knocked on his door I heard him singing inside his room.

“Chanting? I asked when he opened the door.

“No, voice development.”

Some time ago he developed thyroid problems that required two operations that damaged his vocal cords. Now he sounds like someone who has just inhaled helium. But with his Buddhist equanimity he doesn't seem to care and, after the initial shock wears off, neither does anyone else, although he still feels that voice development is something worth spending time on.For the last four years he has been helping to construct the largest Buddha statue in this part of India. Construction began, he told me, after the Taliban blew up the Great Buddha of Bamian statues in Afghanistan. In other words, it is a tit-for-tat statue. It is also very impressive and will be finished later this year.

Sidewalk temple in Sarnath. Somehow the head of the statue will go on top. We had a long cup of tea together. Talking to him I had the impression that one of the happiest periods of his life was when he lived in the small meditation temple in Thailand where I met him. Now that same Thai temple is in the middle of an industrial estate, but in those days it was in a relaxed residential neighborhood. It was also one of the more famous meditation centers in Thailand thanks to the meditation teacher who lived there, Achan Asapa. One of Achan Asapa's students was Jack Kornfield who went on to found one of the largest meditation centers in the USA, Spirit Rock, which is just north of San Francisco. These days Achan Asapa is 103 years old and Jack Kornfield has just released yet another book on meditation, The Wise Heart, where, in the acknowledgments he thanks Achan Asapa for everything he did.

Five days later, March 1, after saying alive 35 days in India, still in SarnathToday is Holi, one of India's many festivals. The festival has some deep spiritual meaning that no one can remember well enough to tell me. These days, as far as I can tell, Holi is an excuse for every man who can afford it to get drunk and throw a paste of colored chalk on everyone he meets. In this part of India women and foreign tourists stay inside during Holi. Going outside means being covered in paste and, especially if you are female, being groped.

Once, many years ago, I went outside during Holi and was seriously groped and covered with colored paste. This time, I stayed in my guesthouse and, with the other guests, had a European breakfast of tea and toast.

Celebrants in the evening of Holi. Holi lasted until noon. After that the paint throwing stopped and everyone went home to change their clothes. Yes, “to change their clothes.” In the late afternoon, when I finally went outside, it was a new India. Holi, I saw with my own eyes, is for many people the only day of the year that they will wear new clothes. People looked over produced, with a preference for sequins, loud colors, and embroidered denim pants, but everyone looked joyous. A few of the well-dressed people were still drunk as skunks. For me, at least, that only resulted in one man, after politely asking me which country I was from, demonstrating his eternal love for all of humanity, including Americans and especially me, by hugging me in the middle of the street, as his friend looked on with embarrassment.

Every day it is a degree or two hotter. The nights are still cool enough to require a blanket, but in the mid-day the sun is now scorchingly hot. A woman told me that in two more months it will be 45 degrees Celsius (113 Fahrenheit) inside and 50 degrees Celsius (122 Fahrenheit) outside.

Two days later, March 3. Thirty-eight days of staying alive in India and still in Sarnath.Thirty-eight days ago I flew from Bangkok to Bodh Gaya. I have since learned that three times a week that same plane travels not only from Bangkok to Bodh Gaya, but also to Varanasi, which is just down the road from here, before flying back to Bangkok. Thus I assumed that when I return to Bangkok I could board the plane in Varanasi instead of Bodh Gaya. But when I telephoned the Thai Airways office in Delhi to ask if this was indeed true, I was told, before the telephone line gave out, that this was impossible. Nothing is impossible in India, so today I visited the Varanasi International Airport to try to make it possible. I made the 40-minute-each-way trip in a motorized rickshaw, which in other places is called a three-wheeled motorcycle. The trip cost me 350 rupees or about $8. In the open-air rickshaw I could observe rural India close up. I once read that in rural India you can actually see the population exploding like a bomb going off and it looked that way today. Many of the cars that passed us were jam-packed with family members such that everyone was sitting on or being sat on by another family member. Buses, motorcycles, bicycle rickshaws, and other motor-rickshaws were likewise packed like caricatures of public transport. The median age seemed to be 14. Where, I wondered, would these people live? What would they do? How will they ever get out of poverty? Valentino, I realized, was probably right. This is the end. For all of its misery and filth, this is the glory day, the apogee, of Indian civilization. No wonder the Indians are always so happy and act like there will be no tomorrow—there won't be!

Let me ramble on a bit more. Here in Sarnath the city fathers have built a sidewalk on both sides of the main road that goes through the historical part of town. To keep people from falling from the sidewalk and into the street, there is a waist-high fence. The locals, who are not city fathers, have somehow decided that parts of the sidewalk are to be used as a public toilet, others parts are to be occupied by vendors, and still other parts of the sidewalk should be used for public housing or as a place to tether the local goats and cows. That, looking at it with Western eyes, is the bad part.

Street scenes in Sarnath. How can everybody look so happy? The good part is that this is India and everything and everyone somehow fits in. There are beggars everywhere, poverty is everywhere, and yet there is something festive in the air. Violent street crime is virtually unknown in this part of India, even if domestic violence and violence against women and children are described daily and in gruesome detail in the local papers. So now, today, jerks like me can walk on the streets with our expensive cameras hanging from our necks in ways that we never could in Brazil or even in parts of the USA. How, I've wondered again and again, can someone who looks like they are starving, just turn away when they ask you for money and you say no? Why are India's poor so mellow? Do they know something that I don't?

The next day, March 4, 38 days in India, and still in Sarnath

As I said earlier, about 60 people attended the non-retreat retreat here. As of today, I am the last of those people who is still in Sarnath. The tourist season is winding down as the HOT-HOT-HOT season winds up. When I came here I slept with two heavy wool blankets. Last week that changed to one blanket, and two nights ago, that changed to one bed sheet. Every day and every night it gets a few degrees hotter.

The heat is changing the way people live. Today in the Internet cafe I was treated to the smell of baking human excrement. The Internet cafe, my only contact with the outside world, consists of four computers, two telephones, and one copy machine that work intermittently. Today someone told me that the irregular electricity supply is thanks to the Indian Government which gives rural areas, like this place, electric power for just a few hours every day. The Internet cafe has a battery which allows for one, and one only, of its computers to keep going through most of the power outages. The guy who works there tells anyone who stops by in the off hours, "No electric now. Electric coming at half-past-five. One computer running."

Anyway, this morning someone used the sidewalk outside the Internet cafe as the public toilet. By 11 AM the blisteringly hot sun was literally “baking the shit.” Unlike say the smell of baking bread, the smell of baking excrement isn't really something that anyone can savor. Plus, it brought a sandstorm of flies into the Internet cafe. It was all I could do to download a bunch of articles from the New York Times and check my e-mail before being totally grossed out by the smell which the man who manages the Internet cafe totally ignored.What a relief it will be, in a few days, to go to the Krishnamurti Center in Varanasi and be in a clean and comfortable place.

Four days later, March 8, 2010, after 42 days of staying alive in India, and now in the Krishnamurti Center in Varanasi.

I now have love and forgiveness in my heart for the person whose baking excrement caused me such distress in the Internet cafe. I'll tell you why I've had a change of heart, but first, some background information.

In India there are three types of diarrhea. 1. Normal Diarrhea, 2, Explosive Diarrhea, and 3, the kind of diarrhea that is everyone's worst nightmare: Surprise Explosive Diarrhea. On my last morning in Sarnath, my worst nightmare, diarrhea type 3, happened while I was walking down the main street of Sarnath in white pants. It was a big surprise. I was on my way to sit in meditation in the very spot that the Buddha himself used to sit in the early morning when disaster struck. If that happens to you, it may help to know that it happened to me and that I lived. Just stay calm. Everything is passing. It is an impersonal event that could happen to anyone. No matter what happens a true gentleman or a true lady never loses his or her dignity, even though it may not look that way to the people around them. If, as they say, you “completely lose your shit” you can remember me and imagine that, even if you don't look it, you have some dignity.

Clearly, I see now, that the person who defecated in front of the Internet cafe a few days ago probably had diarrhea type 3, which was unwanted, explosive, and a surprise. And no doubt I was infected by the hungry flies who came to the baking mess that he or she created on the sidewalk. So it goes. Now at least I can forgive the person who did it. He or she simply lost control. Life can be that way. No matter how much we try to protect ourselves, the unexpected and the unwanted will happen. But after a shower, with detergent, water, and a calm mind, soiled clothing can be washed and restored. If only all of life was that simple.

After such a dramatic start to my last day in Sarnath, my departure, just after noon, went reasonably well. I had been there long enough to know the various motorized rickshaw drivers who hang out around the village's central round-about. I asked a guy I knew there if he could take me for the 30-minute ride to the Krishnamurti Center in Varanasi. He said he could.“No, you can't,” I said when I smelled alcohol on his breath “you've been drinking. You're drunk and can't drive.”

“Not drinking sir,” he pleaded. “Drinking at Holi. Holi finished. Today no drinking.”

“Are you sure?”

“Very sure. Please get in.”

I got in and instructed him to drive me to my guesthouse where my bags were waiting. Once at the guesthouse, after he was invited in, he greeted the manager and his wife, who are local nobility, by pressing his hands to his chest and saying “Namaste.” The manager and his wife nodded and smiled. Everything proceeded smoothly.

My up-scale room in Sarnath and the proprietors, Mr. and Mrs. Agrawal who run the Agrawal Guesthouse. Little did I realize, however, that with her smile the manager's wife was sending a telepathic message to my driver. That message was, “If Mr. Tom gets in that rickshaw with you behind the wheel while you are drunk, like you are now, you are in big, big trouble.”

The guest house managers wished me well, everyone smiled again, and the driver helped me put my bags into his rickshaw. A minute later, however, just out of earshot of the manager and his wife, my driver, now a reformed man, said, "Madame Manager doesn't want me to drive drunk. My brother drives you." At that instant another man appeared out of nowhere and off we went.

Five days later, Saturday March 13, after 47 days in India, still in Varanasi.

Life at the Krishnamurti Center is peaceful and serene. I have my own cottage in a park-like setting not far from the River Ganges. Outside my door peacocks strut and songbirds fill the air.

The main building of the study center, the view from the main building, river view, and one of the cottages.

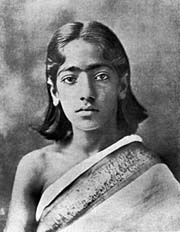

Krishnamurti as a child. This is the Krishnamurti story. Jiddu Krishnamurti was raised, starting in 1909, when he was 14, by the new-agers of his day, the Theosophical Society, to be the new Jesus, the savior of humanity, in the twentieth century. (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jiddu_Krishnamurti) When he was 34, in 1929, he told anyone who would listen that the new Jesus idea was crazy. There were, he told them then, and for the next fifty years, no saviors. If you wanted to save yourself, no one could do it for you. Only you, with a deep-penetrating self-awareness could free yourself from the problems of human existence. The man had charm and a commanding presence that even I noticed when I saw him in 1984 two years before he died at 92.

Krishnamurti felt that if people were going to save themselves they needed to be free of the superstition, fear, anger, competition, and hatred that most of society tells them that they need to survive. To that end he started a few schools around the world. One of them is here, at the southern end of the city of Varanasi which is, by the way, one of the oldest continuously inhabited cities on the planet. The school is a part of the 300-acre Krishnamurti Foundation of India where I'm staying. Located on the banks of the Ganges River, the setting is spectacular. However, you wouldn't know that by looking at the pictures on their home page. To try to remedy that, this morning, after proposing my ideas to the principal of the school, I took some pictures of the retreat center and the school.

Students in their dormitories. Cleaning the Ganges. Pottery class. I began my day there at the morning assembly. At the end of the assembly the music teacher, with the help of a sitar and harmonium, got everyone involved in a prayer/chant that ended with everyone in the room being calm and focused. It was amazing.

After that, walking around, I was struck by how fluent the English of the students is, and by the fact that they all seem to be open, calm, friendly, and exuberant. They told me about the school dogs they had named, about their dorm rooms, their hobbies, and how much they liked the school

Scenes around the Krishnamurti School and a scene from a nearby village. The villagers were also incredibly friendly. The principal, and especially the vice-principal, liked my pictures, so in the afternoon I was asked if I could accompany the students on an outing to the banks of the Ganges where they would collect the plastic litter that had washed ashore.

“This is the Holy River Ganges,” one of the students told me as if I didn't know where I was. We were standing on the banks of the river.

“This is a toilet,” I told him. I knew very well where I was.

He looked at me in shock and told everyone within earshot, “He says it's a toilet!”

“Look, the water is filthy!”

“There, in the middle, they are fishing. The water there is clean.”

“Would you want to eat those fish?”

“No," he admitted.

Working on the banks of the smelly river was hot and uncomfortable, but the students seemed not to mind. They told me that eventually they were going to melt down the collected plastic and make a statue out of it that would serve to remind people of the importance of keeping the river clean.

The next day the vice-principal asked me if I would take more pictures, a lot more pictures. He arranged, because this was Saturday, for there to be a special art class, computer class, chemistry class, and a special basketball practice. Everyone was happy to be photographed and I got to meet more of the students and faculty. Some of the older female students are, naturally enough, drop-dead gorgeous.

There is no corporal punishment here, which is very exceptional for India. Also, exceptionally, the lower grades have no exams. Krishnamurti felt that competition made losers out of everyone, so he got rid of examinations where he could, which was only in the lower grades. Even he understood that no Indian parent would send their children to a school that didn't prepare students for university entrance exams.

After we had finished taking the pictures, the art teacher, who had accompanied me on the last of my photoshoots, and I were walking across the spacious campus, past the Women's College, when he excused himself to look into the canteen that serves the college. In one corner of the canteen were four intermediate school students. They knew that they were not supposed to be in the canteen of the Women's College. It is, I was told, strictly forbidden for the students to eat anywhere except in the school cafeteria, where the food is excellent, and they are likewise forbidden to drink sodas and colas because of what those drinks can do to their teeth. But, because they are teenagers, who always want to bend the rules that adults make for them, the four students had decided to risk it. Now they had been caught and would pay the consequences after the art teacher reported them to the teacher who was responsible for looking after them. By the look on their faces, they had just been sentenced to be shot in the morning.

Generally, the teacher explained, the students at the school are very well behaved. They just needed a little guidance from time to time.

Furthermore, after I asked him, he told me that in the entire history of the school, not one female student had become pregnant. The students, he explained to me, simply didn't think in those terms and if a girl ever did become pregnant it would be “terrible, really terrible.”I guess so.

Meanwhile, for one week, I have eaten all of my meals in the dining room of the study center which comfortably seats 15 people. There I was able to meet an interesting mix of locals and tourists who were dedicated to following Krishnamurti's teachings and who had come here to learn more. One man, an American who is exactly my age, had somehow been awarded a scholarship to stay here for six months. He told me that he spent most of his time in meditation. How, I wondered, could someone spend most of his or her time in meditation at a Krishnamurti center? Krishnamurti didn't like to talk about it, but he had had, from time to time, mystical experiences for most of his life. In spite of that, he always told people that they didn't need mystical experiences and that just by being totally aware, by having what he called a “choiceless awareness,” they could find the true meaning of life. He dismissed gurus and all spiritual traditions as being founded on old, dead thoughts and ideas. He never read any of the great literature of the East, studied under a meditation teacher, or, as they say, “sat in a cave.” Indeed, he liked nothing better than hiking through the woods or getting in bed with a thriller or a mystery novel. Strangely, towards the end of his life he and close friends tried to investigate his mystical experiences. Those investigations have never been made public.

Krishnamurti's theory of meditation sounds okay unless you've actually done intensive meditation practice with a skilled meditation master. The idea of a meditation master or a “spiritual friend” is that he can see when you, the student, is getting off track and help you get back on track. For example, if the student is plagued by a lot of anger in his or her meditation, a teacher might say, “Try thinking loving thoughts about the people you are angry with.” Or if a student finds that he has too much energy that is making him lose concentration, a meditation teacher might recommend doing more walking meditation. One of the great meditation masters of our time, Joseph Goldstein, said that he had tried to learn meditation on his own and just got confused. My experience at the Rajghat Krishnamurti Study Center is that the people who try to teach themselves meditation without a teacher just get confused. Without mystical experiences, we need teachers and spiritual friends to guide us along the path. Mystical experiences are fine for those who have them, but the rest of us probably need more than reading mystery novels or daydreaming about meditation.

16 days later, March 28, one day after leaving India. Back in Bangkok after surviving India for 61 days.

Meanwhile, I had my own meditation to do. By chance, after one last phone call to New Delhi, I was able to change my air ticket to get on the very last plane out of India that Thai Airways flies at the end of the tourist season, March 27. After that day Thai Airways is so sure that no one in their right mind would want to go to hot-hot-hot India that they stop flying there. With a new departure date I would be able to attend another ten-day meditation retreat, this time with Jaya Ashmore, the woman I had made the movie for in Sarnath. The retreat would take place in the Himalayan foothills which would take 17 hours by train to reach.

So after one week at the Krishnamurti Center, which finished with three days of taking hundreds of pictures of the students and then processing them in Adobe Photoshop, I left Varanasi on March 14 for Kathgodam at the base of the Himalayan foothills.

Fortunately, I wasn't traveling alone. By an incredible coincidence, on a shopping trip into chaotic Varanasi, I recognized a woman I had seen on the retreat in Sarnath. We greeted each other like long-lost friends and immediately went to a restaurant for lunch where I learned that she was going to attend the same retreat in the Himalayan foothills. I showed her my ticket and that day she booked a ticket on the same train.

Unfortunately, however, during the train ride I was not able to hear the complete life story of this beautiful and fascinating woman, who, by the way, was the second African-American woman I've met in India, the first being a woman on the Bodh Gaya retreat. I didn't hear my traveling companion's life story because she was carrying a mobile phone which was much more important to her than I was. As we traveled, every time she would begin a story the phone would ring or she would think of someone she had to talk to. As far as I could tell she, her family, and her boyfriend kept a running dialog going 24 hours a day. The rest of the world was just a minor distraction.

Fortunately though, in the Varanasi train station, just before getting on the train, I met a Swiss man who was going to the same retreat. Hans had been given a grant by the Swiss government to study and produce art in Varanasi. He had decided to take a break from his art and do a meditation retreat. As we told each other our life stories we learned that we had studied with many of the same meditation teachers and we had even once been on the same retreat. He tried to explain his art projects to me, but I couldn't understand any of them. One of his projects was about studying how time and space interact by asking gurus to guess his age on his birthday as he took their pictures. Whatever. Artists can do anything they want and the world will forgive them.

Getting to Kathgodam from Varanasi involved two six-hour train rides with a five-hour stopover in Lucknow, about halfway. For reasons that no one could explain, all of the trains were all exactly on time. Someone told me that this is was a first in the history of the Indian Railways, India's largest employer.

The train arrived in Kathgodam (pronounced cot-go-damn) which is the last town before this part of the Himalayan foothills, at seven in the morning. From there it was another 90 minutes by land-cruiser to the Sattal Christian Ashram, high up in the foothills. Strangely, when we got off the train we found that 12 other people who had been on the train with us were also going to the retreat, including two people who had been there before. They kindly arranged the transportation. Soon I found myself sitting next to a young woman from Israel who was kind enough to explain to me what it would take to bring peace to the Middle East. She was a member of the small minority of Israelis who thought that the Palestinians were actually human beings. Because of this, she, and members of her peace group, annually volunteered to help Palestinian farmers, who had the courage to ask them, to pick olives. She believed that until the Israeli government developed a benign social consciousness and abandoned the illegal settlements, there would never be peace. Interestingly, she also told me that Christopher Titmuss had probably done more than anyone else to help take the teachings of the Buddha, who helped erase attachments to nationalities, history, and boundaries, to Israel.

When we finally reached Sattal, I immediately understood why this was paradise to the Indians from the central plains. A) it was cool. B) it was quiet C) there were crystal-clear lakes all around us D) there were pristine forests everywhere. This was a great relief.

One of the cottages and the grounds of the Sattal Ashram. It is a Christian ashram and as such the enthusiastic Methodists have plastered the walls with paintings of Jesus. Looking at the paintings one would have to conclude that Jesus was an Italian hippie who lived in the woods outside Rome. More pictures of the Sattal Ashram are here: https://flic.kr/s/aHsjY8QQfV

If there were any problems, it was with the wild animals. The local monkey population was sometimes aggressive enough to steal food from people's plates as they (the humans) ate outside. And one night when I was doing walking meditation at the edge of a dark forest, I heard a large animal approach me through the brush. I got scared and went back to the main building. The next day I was told that a leopard had stopped by looking for food.

Another time I was walking back to the main grounds, near where some cars were parked, and a troop of aggressive-looking monkeys blocked my path. An Indian man, also a visitor, standing just outside one of the buildings, saw what was happening and promptly threw a rock at the monkeys. Unfornately, the rock missed the monkeys and broke a car window. That was enough so scare the monkeys away and, I'm sure, frighten the Indian man who had just broken the window.

***After doing at least one hundred ten-day-or-longer meditation retreats over the last 30 years, I came to this retreat without a lot of expectations. I got a big surprise, but first some background information.

Throughout the history of meditation in the East one of the big problems has been sleepiness. Bodhidharma, the man who brought Buddhism to China 1,500 years ago, is said to have gotten so tired of falling asleep in meditation that he ripped his eyebrows off, threw them on the ground, and from them sprang up the first caffeine-packed green tea leaves that have been used ever since by Zen meditators to help them stay awake in meditation.

Other people have meditated with a sword propped up against their throats or while sitting on the edge of a deep well. I haven't tried the sword or well trick but I've tried everything else — from vitamin therapy, to double cappuccino, to standing up, to breathing exercises.

Fortunately, there is Jaya Ashmore. This former Harvard Divinity School student has, she claims, found the answer to the millennium-old problem of sleeping during meditation. She teaches that sleeping is not the problem, rather it is the solution. To that end, when she teaches meditation every student is asked to bring, or is supplied with, a light mattress to lie down on. Thus her meditation halls look something like a kindergarten class at nap time. She asks that before every 45-minute meditation period students decide if they want to sit up or lie down. If they chose to lie down and they fall asleep, she lets them sleep, even if they snore. The problem is, according to her, that people are often not well-rested. It's that simple. She believes that given enough rest, they will be able to develop deep states of meditation while lying down. And because they are lying down and not worrying about keeping their spine straight or anything else, letting gravity do its work, they may even be able to go deeper into the meditation than they could if they were sitting up. (See her website, Opendharma.org for more details.)

I had heard this theory from her enthusiastic students for years and had dismissed it as new-age wishful thinking. But there I was, on the retreat, with a wonderfully inviting thin mattress in front of me. How could I resist?

For the first three days I was, just as a previous meditation master had told me I would be, groggy and with a headache from too much sleep. But then on day four something shifted and I noticed that for one meditation period I stayed awake, on my back, for the entire period. Another meditator reported that even though she had suffered from insomnia for years she found that she could now sleep virtually all day in the meditation hall and then sleep soundly at night. After a few days though, she too started staying awake in the meditation hall.

Then, by day five, my headaches and backache vanished to be replaced with what felt like a deep mental clarity and alertness. Why, I wondered, hadn't anyone ever told me this before? None of the “meditation masters” I had studied with over the last 30 years in the USA, Japan, India, Thailand, Nepal, and Sri Lanka had ever considered that perhaps one reason why people fell asleep in meditation was that they were, on a deep level, tired.

Jaya taught that the proper posture for lying-down meditation was to keep the knees higher than the hips and the ankles higher than the knees with the head flat on the floor. To bring more energy to the posture, she suggested that people could use a posture from the Japanese art of Jin Shin Jyutsu. Here one hand reaches over the shoulder and hangs onto the muscle between the neck and the shoulder while the other hand rests on the joint between the hips and the thigh, almost touching the pubic area.

With increased mental alertness, tensions that I had been unaware of surfaced. Jaya taught that when anger arose one remedy for it was to generate thoughts of loving-kindness (metta) right there and then. (Other meditation teachers I have studied with urged students to investigate anger and hold off on the loving-kindness until later.) I found this useful and I started dedicating one meditation period a day to doing nothing but trying to generate thoughts of loving-kindness for, well, everyone. I hadn't done this since I had left the jungles of South America where the psychotropic plant ayahuasca had made such meditation wonderfully ecstatic. Strangely to me, I found that even without ayahuasca my concentration was deep enough that I once found myself covered in a stream of joyful tears. How about that?

Achan Cha, a Thai forest master, once said that one has never really meditated until he or she has cried a river of tears.

The other big benefit of doing so much meditation while on my back was that the element of pain was now gone. Long-time meditators don't talk much about it, but one thing that they are always aware of is pain in the knees, hips, and backs. Sitting up all day, day after day, in the cross-legged position for Asians and Westerners alike has an element of pain and discomfort that never goes completely away. The pain was now gone and replaced by a general sense of well-being.

When the retreat began I was sleeping from 10 PM until 4 AM, getting up two hours before the wake-up bell to do a little yoga. By day four, 4 AM had changed to 3:30 AM, and by day eight that had changed to 2:30 which gave me enough time to do 90 minutes of meditation and some yoga before the first meditation period at 7:30 in the morning. Four and a half hours of sleep was enough now that I was, as Jays says, “deep rested.”

How about that?

Meanwhile, I tried to ignore everyone around me. Jaya has many strengths, but one of them is not disciplining other people. A few people never realized that if they were going to get anywhere with this style of meditation they had to put every moment of wakefulness into the practice, into cultivating constant mindfulness and attention. I tried not to notice the people who read books during the breaks, who snuck off to be with their lovers in the woods, or who spaced out studying the monkeys or taking pictures. If, one meditation master said, you want the medicine to work, you have to follow the directions written on the bottle. Even while lying down there aren't any shortcuts. Although I never asked her about wandering meditators, my guess is that Jaya would say something about a caterpillar never becomes a butterfly before it's supposed to. It might also be true that Jaya has more patience, love, understanding, and compassion than I do.

At the end of the retreat almost everyone said that it had been a life-changing experience.

The retreat ended on March 25, exactly two days before Thai Airways made its last flight of the season out of India. I had 48 hours to cross the northern part of India to return to Bodh Gaya and get on that plane.

Step one was easy. Because Kathgodam is at the end of a rail line, the trains leave on time. My train, a second-class air-conditioned sleeper, left on time at 9:50 the night the retreat finished. It delivered me to Lucknow, about halfway to Bodh Gaya, at six the next morning, which was the perfect time to have breakfast with Hans, the Swiss artist who lives in Varanasi. We said goodbye at 8 as he hurried to catch his train.

My train was scheduled to leave at 12:30 PM. But when I inquired about it at ten that morning, I was told that at present it was five hours late! Would five hours stretch to ten hours? Would it be one of those phantom Indian trains that are “lost?” What to do? I went to the station master and was told that another train, bound for Calcutta that would stop in Gaya, would depart at 11:45 that morning and that if I bought a first-class ticket I was sure to get a seat.

I hurried to the ticket counters. Once there, it took me only a few minutes to find the first-class window mainly because it was the only window that wasn't totally jammed up with people elbowing each other to get to the window. The clerk seemed happy to see me and a minute later the ticket was, in record time, in my hand.

I ran out to the platform and saw that my train was already at the station. I found the conductor and showed him my ticket. “There are no first-class seats on this train,” he told me.

“Second-class air-conditioned is fine.”

He searched his computer printouts for an available seat. As he did, I felt like someone on a reality TV show who is helplessly waiting to learn if he is going to stay in the game or get sent home. Was I going to be waiting at this station for five or ten more hours?

“Nothing is available,” he told me. He was serious.

“But I have a first-class ticket.”

“What can I do?” he asked me sincerely. “There are no seats.”

“What should I do?”

“Get on the train; it is moving.”

I had never thought of that: “get on the train; it is moving.” The train was definitely moving.

Suddenly I was running alongside the train pulling my luggage behind me. Just then, as the train started moving as fast as I could run, someone appeared out of nowhere and helped me push my heavy bag-on-wheels into the moving door of a non-air-conditioned sleeper. I followed the bag into the train with a Tarzan-inspired leap. A more dramatic departure has seldom been seen in India.

My worst nightmare had suddenly come true: I was sentenced to ride in the lowest class of train in India at the beginning of the hot-hot-hot season. Brace yourself, I told myself, this is going to hurt.

As my heartbeat and breathing returned to normal, my eyes slowly adjusted to the dim light inside the train. Where am I? I pulled my bag into the first of the nine open-ended compartments of the car.

Indian “General Sleeper” trains consist of compartments of two rows of three tiers of sleeping planks (triple-tiered bunk beds) facing each other with two other berths facing them so that eight people share a small cabin. In theory each car sleeps 77 people, but in reality they can get much more crowded.

I looked for a place to sit down. “That seat is taken,” a man about 65 told me, “but you can sit down.” I thanked him and sat down.

He wasn't doing any better than I was. A few months ago he had booked a seat in an air-conditioned car and been placed on a waiting list. He showed me his ticket for an air-conditioned coach, which he had paid for. Unfortunately, he told me, he was still on the waiting list.

Soon the conductor appeared. He explained that we could sit in these seats for a few more hours until the train reached Varanasi, at which time people who had paid for our seats would board the train and occupy them. My new-found traveling companion, who later told me that his name was Pierre the Great of Paris, told me that during the previous night, he and his wife, for the first time in their lives, had slept on the floor of the train. So things were going to get rough, but just now I realized that this gentleman would look after me. Things were fine. A few minutes later a vendor, who had somehow secured the right to sell lunch to the passengers on the train, was passing through the car. I requested a vegetarian lunch. He then shouted all the orders from my cabin into his mobile phone. Those orders would be delivered to the train a few stations up the line.

I bought some peanuts and listened to the old man tell his story. He and his wife were, just now, returning from Haridwar, where they had joined the largest religious gathering of human beings on planet earth for a celebration that occurs every 12 years to mark the auspicious deeds of Lord Vishnu. They call it the Kumbha Mela.

“Did you see the naked sadhus and naga babas?” I asked.

“We did not go there to see naked people,” he said with the same humor and seriousness that he said everything. “We went there to bathe in the holy river Ganges.”

“There I think that the river is still clean.”

“Yes, very clean.”

Now he was returning to his home in Calcutta which would be, if things went well, require only one more night and one more day on the train. I asked him how life in Calcutta was for him.

“Noisy, polluted, crowded, and dirty,” he said. He was the first person I had ever met from Calcutta who spoke the truth.

“But,” I said, “I sense that you are somehow happy.” He had a very serene way of carrying himself.

“When I reach my home, my daughter's children will come to see their grandfather. When I see them my heart will fill and overflow with love and happiness.” He was serious.

He had arranged a marriage for his daughter. “We are Brahman's,” he said, referring to his status as a member of India's highest caste. “If I hadn't found a suitable Brahman for her, the other relatives would have stopped talking to us.”

“Is she happy?”

“Very happy.”

“And your wife?”

He told me that before their marriage he and his wife had never seen or talked to each other, but that now they had been together for 45 years.

“And it's okay?”

“If she says something bad to me, later she cries,” he told me. “She is always with me, looking after me. Now you see who she is, but when we were married she was very, very beautiful.”

“Of course.” She was fat, gray, and wrinkled.

After lunch he told me that I should take a rest, which meant that he was tired of talking and wanted to take a nap. There was one berth, the top of the three berths, that was free. I climbed up, somehow got comfortable, and read a book. It was, I was told later, 41 degrees Celsius (104 F) outside. Inside, because of the heat radiating through the roof of the train, it was probably much hotter. But it was a dry and clean heat as rural India passed by outside the train. This would be, I thought to myself more than once, the wrong place to have surprise explosive diarrhea.

The view from the top berth. As the sun was setting, I put my head down to look out the window and saw that we were crossing the Ganges River. Our next stop would be Varanasi where the people with real tickets for our seats would board the train.

Varanasi is a major stop, so I knew that we would be there for at least 15 minutes.

As soon as the train came to a stop, I climbed down from the top berth, ran out onto the crowded and confused platform, and looked for the conductor in charge of the air-conditioned coaches. He was easy to spot — he wore a black dinner jacket, black pants, black leather shoes, a white shirt, and a black tie. I showed him my ticket and again he looked through his print-outs of the seats in the air-conditioned section. As he did this I wondered if I had recently accumulated any bad karma by deliberately killing insects, by not giving to everyone who asked me for money, or by being rude to any of the endless stream of people who asked me every day where I am from.

A few seconds later the conductor silently, as my heart beat at double speed, wrote on my ticket the berth number in the two-tier, not three-tier, air-conditioned coach where a comfortable and cool bed with white sheets was waiting for me. Thank you Buddha, Jesus, and all of the saints and beings who have postponed ultimate nirvana, Boddhisattvas, to help those of us stuck in the wheel of continuous births, samsara. I promise to be compassionate to all sentient beings for the rest of this birth and in all future births. Amen. Hallelujah.

I ran back into the general sleeper coach where I had spent the previous eight hours. “My berth,” I announced to Pierre the Great of Paris, “opened up in AC.”

“How many berths?” he asked me.

“I don't know, but you should ask. I wish you good luck. It was very nice meeting you. I wish you well.”

With that I was gone. A few minutes later, I plugged my computer into the 220-volt outlet that is, these days, available in air-conditioned coaches in India, and watched a movie.

India, as so many travelers have said before me, can be bad, very bad. Later, almost instantly, it can be good, very good.

A woman sharing a berth near me asked me where I was going. I told her, “Gaya.” She strongly advised me against attempting the thirty-minute taxi ride from the rail junction of Gaya to the village of Bodh Gaya that night. She urged me to contact the station master in Gaya who, she assured me, would help me.

“Are you from Gaya?” I asked.

“No, never in many, many, births would I ever be from Gaya,” she said seriously.

(Once, when I had called computer support in India and told them that I was going to Gaya, the person was amazed — why would anyone, he wondered, voluntarily go to Gaya?)

I thanked her for her advice. Shortly after that a man who was actually from Gaya wrote down for me the names of three hotels that were near the train station; he circled the “VIP” hotel. I thanked him as well.

The train reached the Gaya station at 1 AM. As soon as I stepped off the train I was surrounded by taxi drivers who wanted to take me to Bodh Gaya. I ignored them.