From Phnom Penh

by

You Sokhanno and Thomas Riddle

July 1981

I

I am You Sokhanno, a Cambodian refugee. For the last five months I have been living in the Philippines Refugee Processing Center on the peninsula of Bataan, about three hours drive north of Manila. There are 17,000 refugees here from Laos, Vietnam, and Cambodia. Almost all of us have been approved for permanent resettlement in the United States. I live here with my mother, two sisters, two nieces, three nephews, and one brother-in-law. At 21, I am the youngest girl in the family.

This is the story of my life in Cambodia, the death of half of my family, and of my life as a refugee.

I was born in Phnom Penh, the capital of Cambodia in 1960. I remember growing up with my five brothers and three sisters. My father was a clerk in an office and my mother was a housewife. We were a middle-class Cambodian family; we did not have money to spare, but still, all of us were able to attend school.

When I was six years old I started school. I liked it very much and always did well. After three years in the primary school, I passed the entrance examination to the only government-run English speaking school in Cambodia. I was the scholar in the family, and my parents always let me know that they were very proud of me. They said that their hopes were in me.

When I was 13 my father died. For a month he struggled with malaria and cancer while my mother and I took care of him. One day he told me that he did not have much longer to live and that he hoped that I would get a good education. I promised him that I would do the best I could. The next day he died, and his death was a great sorrow to us all.

II

On March 18, 1970 the Royalist Government of Prince Sihanouk fell and a right-wing politician by the name of General Lon Nol came into power, but our lives stayed the same. Four of my brothers were soldiers with Lon Nol, and one was even a colonel. I remember those years (1970-1975) as happy years. We had a television, and I can remember watching Superman.

During those years I heard about Pol Pot, a guerrilla fighter. He had once worked with Prince Sihanouk's government, but he had formed his own army in the Cambodian jungles. We never thought that his guerrilla band would one day take over Cambodia.In 1973 I heard gunfire outside of Phnom Penh, and I saw pictures of the fighting on television, but I continued going to high school. In 1974, the Khmer Rouge (the soldiers of Pol Pot) began shelling Phnom Penh. One of my girlfriends was killed as she was taking a bath. She was a very pretty girl and I saw her cremated. We were frightened, but I was young and didn't know what to do. Some of my friends went to America, but we did not have enough money for that. I had book with their addresses in it, but I lost it.

At the end of 1974, the shelling increased. We built a bomb shelter out of the sandbags in our house. The bombing and the tremendous flow of refugees caused by fighting in the provinces made life in the Phnom Penh difficult for everyone.

Finally, when the troops of Pol Pot overtook Phnom Penh on April 17, 1975 we all felt that peace had come. Because of that and because we were afraid, we cheered the soldiers in their black uniforms as they carried a white flag that said, "Peace has Come." We thought that the fighting that had gone on since 1970 and caused so much destruction in the provinces had come to an end.

A few hours later I saw a liberal soldier, a supporter of Lon Nol, shot and fall dead on the road. That was the first time I had seen anyone die; I was 15 years-old. Chills ran up my spine. I ran back home as quickly as I could and told my family what I had seen. There was not going to be peace.

Later I learned that on that day the Khmer Rouge soldiers were traveling around the city in trucks gathering up all the men who were wearing the uniforms of Lon Nol's army. The Khmer Rouge took them to Phnom Penh's stadium where they shot them.

As I was telling my family what I had seen, in the road two soldiers of Pol Pot appeared at our gate. They told us that for our own safety we would have to leave the city for three days. They said that anyone who stayed would be killed.

The entire city was being emptied. We packed a few things and joined the long lines out of the city. My oldest sister carried most of our gold, platinum, and jewels around her waist. We had kept our savings in this manner as was the Cambodian custom.

The soldiers allowed the people to travel only on one road and the entire city seemed to be on that road. The hospitals were evacuated as well. I saw sick people being carried in hammocks, some with bottles of serum attached to their makeshift beds. Soldiers prodded people with bayonets to keep moving, but the road was so crowded that everyone had to travel very slowly. Many people did not want to leave their homes; I heard that some of the people who stayed behind were later killed by the soldiers.

As we left the city we looked for two of my brothers who were soldiers and living in their own homes with their families. Only later would we learn what had happened to them.

My family traveled as slowly as possible. We thought that since we were only going out of the capital for three days we should stay as close to the city as we could. That first night we slept outside the Vealsbauv temple. We stayed there for ten days waiting to return home and then we understood that we had been tricked. City officials and soldiers of Lon Nol were asked to write their names down so that they could go back into the city and work, but it was just a trick: they were killed.

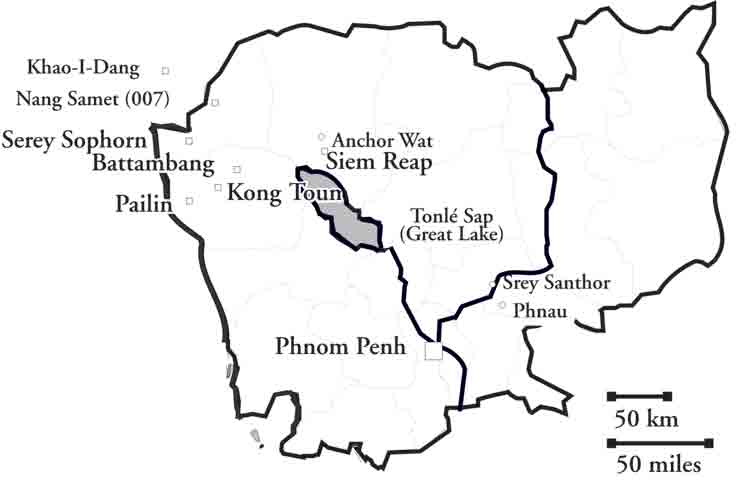

On the tenth day the soldiers of Pol Pot told us that we would not be returning to the city and that there was work to be done in the country. My family decided to go back to Phnau, the native village of my parents. We traveled 30 kilometers to the Mekong River, got on a boat, and went up the Mekong to Srey Santhor. We traveled by oxcart from there to our native village.

When we arrived in Phnau our relatives there did not greet us with their usual warm hospitality, instead, they seemed suspicious of us. Later they told us secretly that officials of Pol Pot had told them to be wary of people from Phnom Penh.

Shortly after our arrival in Phnau the soldiers called us to a general meeting. We were told to forget the ways of the city and to become farmers. Girls had to cut their hair short and rid themselves of all western ornamentation such as long fingernails and western clothes. We had to dye our clothes black. We were put in groups of ten and in sections of fifty. The leaders of the sections were people who had cooperated with Pol Pot for at least five years. We would come to know the leaders of Pol Pot's regime as the Angka. Angka was the Cambodian word for organization. After Pol Pot came onto power everything was under the control of the Angka. The people from the city came to be known as the "April 17 people " and the people from the country were known as the "old people." We were told that as April 17 people we could not wander from the village.

We worked in the rice fields. The women and the men worked together, with the young children being taken care of by the older people, like my mother. Having spent most of life in the city, I knew nothing about the planting and caring of rice. Planting rive is tremendously hard and tedious work and requires long days in the hot sun or in the cold rain. I hated it.

My oldest sister's husband had been a professor in Phnom Penh. When we first came to the country he had been able to pass himself off as an ordinary worker, but then, we believe, someone from Phnom Penh told the Angka that he had been an intellectual. He was told that he would go away to "study." He took his clothes with him and left us. We never saw him again and believe that the Angka killed him.

We stayed in our native village for ten months and then Pol Pot ordered the April 17 people to go to Battambang Province, the largest rice producing province in Cambodia.

We took an oxcart from Phnau to the Mekong River and then got on a crowded steamer. A few hours later we passed Phnom Penh. All of the April 17 people crowded to one side of the boat so that we could see our beloved home. Tears came to my eyes: where there had once been a beautiful beach, now banana trees had been planted; what had formerly been flower gardens were now mountains of rusting cars and motorcycles that people had left behind. We could see that many buildings had been destroyed. So many of us were pressing against the windows of the steamer that the boat almost tipped over. The Khmer Rouge in charge ordered everyone to go back to their places and told us that we would never be allowed to go back to our city.

We traveled by boat for twelve more hours or about a third of the way to Battambang. After waiting there for three days we got on a train and twelve hours later arrived in Battambang Province. From there we went by truck to the tiny village of Kong Toum where we would stay for two and a half years.

When we first got there we had enough food. We had rice porridge for lunch and cooked rice for dinner. We picked a wild green leafy plant for our vegetable. After six months we were forced to eat collectively. By that time the food situation had gotten much worse: we ate the trunks of banana trees, the roots of papaya trees, and watered down rice porridge. I started to lose weight.

We were forced to go to meetings almost every night and because of the threat of having our food taken away, no one resisted. The meetings were very boring so I sometimes fell asleep, but because I was so young, no one really minded. Frequently at these meetings we were told by the Angka, "All of us must be the masters of ourselves, we have to work hard and be serious in our work if are not to receive foreign aid."

The children were raised collectively; they slept together and sometimes worked together in the fields. We called the building they stayed in the "children's barracks." They were taught that the Angka was much greater than their parents. The Angka tried and sometimes succeeded in instilling a tremendous sense of loyalty to the Angka in the children.

Teenagers were put in a work battalion called the "mobile brigade" or "first strength." We all had to live apart from our parents. We would travel around the countryside staying in different locations from one week to three months doing things like planting rice and digging irrigation canals. I carried my clothes, blanket, and cooking utensils in a small backpack. It was very difficult for me to see my family: we had to get special permission from the group leader to see our families and if someone left without permission a day's ration of food would be taken away from him.

In the mobile brigade the woman slept in one shelter and the men in another. There was not supposed to be any contact between the sexes, but I heard that one official of Pol Pot raped some girls.

In 1977 I worked with the mobile brigade planting rice in the rainy season. After days and days of working in the rain, I got sick. I asked the group leader for permission not to work. He wanted me to work and said, "You are not really sick comrade. You will not eat unless you work."

I continued to work in the rain and one day I passed out while working. I was taken from the field to the village hospital by oxcart where I was given an injection of what they told me was vitamin B-12, but what was really something that the nurses of Pol Pot had concocted. I developed a large abscess on my hip from the injection. They told me that they would have to operate on me in a larger hospital. Going in to the hospital I knew three things: that they had no anesthesia for the operation, that most people who entered the hospital died there, and that I was going to die. I told my mother where I wanted to be buried and asked her to plant some flowers on my grave. My mother thought that I was going to die also and she cried. Five people had to hold me down while they operated.

Surprisingly, after the operation I was still alive. The nurses urged me to remain in the hospital and recover, but I knew better: I had been in the hospital once before and had seen many people die of dysentery. Sometimes people pretended to be sick to keep from working and went to the hospital where they developed dysentery from the other patients and died. I left the big hospital as quickly as I could and went back to the small hospital near my home where my mother was able to take care of me.

I was able to bribe the nurses with a new sarong and some gold to give me some antibiotics, and I slowly recovered. I spent a total of six months in the hospital. When I finally left the hospital, I went back to the mobile brigade.

Only one of my brothers was not married when Phnom Penh fell. He had come with us to Phnau and then to Kong Toum. In Kong Toum he and I were placed in different divisions of the mobile brigade. With the mobile brigade he traveled far away from us and only later did we hear what had happened to him. During a severe food shortage he became malnourished and his body swelled up. He pleaded with his section leader for permission not to work, but he was forced to work. They were clearing a swamp to plant in, and while working in water up to his chest he passed out. We heard that he died on the way to the hospital, but we do not know the details of his death or what happened to his body. He was 30 years old.

My sister-in-law was from Phnom Penh. She had been a housewife there. She came to Battambang and didn't like the life on the farm. Also, she believed that because her husband had been a nurse in the military he would soon be killed by Pol Pot. One morning she left home with a piece of rope that she said she was going to use to bundle wood together. We could not find her that night. We looked for her again in the morning. Later that day the Angka section leader came and told us that he had found her in the forest. We went there and found that she had hanged herself. We could not find enough wood to cremate her so we buried her. Her husband, my brother, cried a great deal.

What my sister-in-law had believed became true. Her husband was taken away from us and killed by Pol Pot.

I lost four brothers and one sister. The sister who died was working in a field when she cut herself with a shovel. She was taken to a hospital. It was only a small cut and it would have been easy to treat with antibiotics, but the Angka believed that people should be treated with herbal medicine so my sister developed tetanus and died a week later. She was 27. We cremated her.

Originally we were told to dye out clothes black, but later we were given white cloth and no dye. I remember seeing white thin silhouettes planting rice in the fields. In Cambodia we wear white to mourn our dead relations before they are cremated and then after they have been cremated or buried, as the case may be, we wear black and white or just black clothes. To me, we were already dead and dressing in white to mourn our own deaths.

All of us were so terrified that no one resisted. If we resisted, what could we do with no weapons?

We don't really know what the Angka's plan was, but we believe that Pol Pot was trying to starve everyone from Phnom Penh to death. We worked hard and harvested a lot of rice, but our rice was taken from us and we starved.

When the rainy season came in May of 1978 I was working with about 170 other teenagers in the mobile brigade going from place to place planting rice. When we first came to a place we would erect open shelters with corrugated iron roofs that we had transported by oxcart from the previous camp. We worked outside all day in the torrential rains and became soaked and cold. Returning back to the shelter we found no comfort in the dampness and mud. When the meal bell rang I remember going for just one plate of watered down rice porridge and a small bowl of wild vegetable soup. When the bell rang the second time, all too soon, I knew that the work would begin again and that I had not had enough to eat. I thought of the life I had known in Phnom Penh and how easily I had lived. We had owned a car, a television, and a refrigerator with food in it.

I became very thin and malnourished. One day after I collapsed while working in the rice fields I was able to convince the man in charge to send me to the hospital. When I got out of the hospital I was allowed to live with my mother and work in the childcare center. The food shortage continued. Some of my neighbors in Kong Toum died from starvation.

Starvation. Most people swell up and later die in their sleep, others get skinny and die. I can still hear dying people shouting out for food. I have met people who said that they ate babies. Other people, including me, ate insects; before a rain it is easy to catch moths. Also we ate mice and rats.

Once I wished that I was a rat so that I could crawl into a warehouse and eat grains. I dreamed constantly of food. We had banana, papaya, and some other fruit trees near our house that the Angka said were collectively owned, but sometimes I went out at night and stole them. Everyone did what they could to stay alive.

In September of 1978 we heard from my sister, Sokhen,whom we hadn't heard from since 1975. She had married a man in Pailin Province two weeks before Phnom Penh fell and we had no idea what had happened to her. A man from Kong Toum located her by accident as he was returning home with wood he had chopped on a forest that was three days by oxcart from Kong Toum. He had stopped in a village and asked for a glass of water. My sister gave him the water and asked him where his native village was. He told her that he was originally from a village near Phnau and that some Phnau people were living near him in Kong Toum. My sister said that she too was from Phnau and asked the man who the Phnau people in Kong Toum were. The woodchopper said that it that it was us. My sister gave the man a letter. Reading the letter we learned that since we had seen her last my sister had given birth to two children. We cried at the good news.

During the harvest time the food situation always got a little better, but still, we never felt as though we had enough to eat. In October of 1978 the Angka told all of us who worked in the childcare center that if we wanted to we could work in the warehouse grounds from 7 p.m. until 11 at night separating the rice seeds from the cut stalks of rice and that each of us would be paid one coconut for our services. Almost all of us agreed to work.

I decided that I would steal some rice while working so I sewed a big pocket into one of my sarongs. That night, before the work began the Angka section leader warned us that anyone caught stealing rice would be severely punished. I was not deterred, however, and an hour after the work had begun I had secretly filled the pocket of my sarong without any of the guards noticing. Walking carefully, so as not to reveal what I was carrying, I pretended that I was going out into the shadows to relieve myself and sneaked home. Fortunately, we lived near the warehouse. When I got home I found that I had stolen enough rice to give the five of us a good meal. Even though I had succeeded my mother and sister warned me not to do it again. I promised them that I wouldn't do it again unless I had the chance and went back to work

After another hour I had once again filled the pocket. Again I pretended that to step into the shadows to answer the call of nature. I hurried into my house and climbed up the ladder to the sleeping loft. Halfway up the ladder, I heard footsteps behind me. I raced up the ladder, threw off the sarong, and got under the mosquito net with my mother. I knew that whoever it was would not be able to see me in the darkness. Unfortunately he had a cigarette lighter. He lit it, saw me, and told me to come out. I didn't move. A person caught stealing rice could be beaten to death.

He reached into the mosquito net, grabbed my arm, and pulled me out. He asked me my name and if I had stolen the rice. By that time I knew that I had been caught so I answered him truthfully. I was crying.

He said that he was going to take me to the section leader. He pulled me across the room. I got down on my knees and clasped his feet. I pleaded with him saying that I had only taken the rice because I was tired of eating the Angka's watered down rice porridge.

Twice he hit me hard on the back. He was an educated man from Phnom Penh, but the section leader was a woman and he was her lover. I promised him that I wouldn't steal rice again.

The anger in his voice subsided and he said that he would let me go because it was my first time. He tore the pocket I had filled with rice out of my sarong and left.

That was the last time I stole rice.

In November there was an unusually heavy rain. It rained hard enough to rot the young shoots of rice we had planted and wipe out the rice crop. Because we had nothing to do, the Angka decided to move us.

A truck took us 40 kilometers to a village west of Battambang City called Paoy Samraong. When I first got there I was assigned to the fields. One day I collapsed in the fields and I was once again assigned to work in the care center. At that time I looked like a cross between an old grandmother and a monkey. I can laugh about it now, but at the time I had almost starved to death. There were times when I thought I was going to die.

My job was to take care of the babies while their mothers worked. There were only babies because even small children were made to work.

On January 7, 1979, the Vietnamese Army captured the city of Phnom Penh, but we did not know that until the Vietnamese reached Battambang on January 11. I didn't see the Vietnamese and Khmer Rouge soldiers fighting, but I heard them. All of us were happy to hear that the Vietnamese had come and when the supporters of Pol Pot fled to the jungles we thought that we were going to be free.

The Vietnamese protected us from Pol Pot's soldiers and they did not manage us the way the Angka had, so when it was harvest time we worked as individuals and not collectively to harvest as much rice as we could to keep from starving. It took my sister and I one month to harvest ten 60 kilogram bags of rice, or enough rice to keep my family alive for five months. People who had oxcarts were able to harvest much more than we were, but we had to carry the rice on our heads from the distant fields to our house. We worked every day as hard as we could. When we had to walk to the farthest fields we were afraid that the soldiers of Pol Pot were going to kidnap us.

When Pol Pot had taken control of Cambodia he had banned the English language. Because of that and because I had seen educated people killed, I had pretended to be totally uneducated during the Pol Pot regime. So one day when I used an English word while talking to a friend of mine she was very surprised. She said that she too had feigned ignorance and that she would lend me an English book that she had kept hidden for four years. The book was Essential English.

One of our relations used our new freedom to visit his girlfriend. During his trip he met my only surviving brother in Kdol, a village south of Battambang. We decided to join my brother. On the eleventh of February, we put our rice in an oxcart which we had borrowed from a distant relative, and began walking to Battambang city. After one night and one day we had walked through Battambang city and then four more kilometers to the village of Kdol where we stayed in a big Buddhist temple with my brother and his family. Far from the jungle we believed that we would be safe. More than one hundred people stayed on the temple grounds.

My brother wanted all of us to go back to Phnom Penh and get jobs. But the bus driver was Vietnamese; he wanted the bus fare to be paid in gold, and we could not afford it. We started a small vegetable business where we sold vegetables for rice or gold.

After waiting seven months my brother decided that he, his wife, and their children would walk the 350 kilometers to Phnom Penh. He had a little gold that he thought would last him until he found a job. We would have gone with him, but I was still too weak to travel that far and we did not want to be a burden to our relations in Phnau. Also, we had very little gold left. Later I heard that my brother was not able to get a job and that he is now a rice farmer.

We met a cousin of ours who told us what had happened to two of my brothers. One had been a colonel and the other a lieutenant in Lon Nol's army. They had left Phnom Penh together in a car along with some other military officials. After the first night, the lieutenant was afraid to be traveling with such high ranking officers so he left my oldest brother, the colonel. A few months later, however, they met again and they eventually settled in adjoining villages. My cousin stayed in the same village as the colonel. One day the lieutenant went to visit his older brother. A young man told him that the colonel and his family had gone off to study. The young man explained that the Angka would take care of all of the needs of people who went off to study and persuaded the lieutenant to go as well. The lieutenant took all of his family with him when he went to study, but it was all a ruse. They were all killed.

Shortly after my brother and his family went to Phnom Penh my oldest sister got a job as a teacher 50 kilometers from Battambang in the village of Serey Sophorn. She knew that from Serey Sophorn we might be able to escape to Thailand. We did not want to leave Cambodia, and even now we hope to return home if peace ever returns there, but we felt we had no choice. We believed that under the Vietnamese our lives would not improve and that we would eventually run out of food and starve to death, The nine people in my family who were still alive moved to Serey Sophorn.

My sister was paid in rice by the Vietnamese, but it was not enough to keep us alive. After one month we made our move. A distant relative of ours was a smuggler he would go to Thailand and smuggle things like clothes, food, soap, rice, etc. back into Cambodia. He agreed to take us to Thailand.

On the 31st of September, we left Serey Sophorn in the early morning. Because it was on the middle of the rainy season the jungle was not so heavily patrolled, but the path was very muddy. Along the way we had to watch for Khmer Rouge soldiers, Vietnamese soldiers, and land mines. Once we hid from Vietnamese soldiers. Including our guide there were ten of us: six adults and four children. One of the children was the four year-old only child of my sister-in-law who had hung herself. She had had dysentery for one month. One of my oldest sister's friends had brought some medicines with her from Phnom Penh in 1975 which my sister was able to exchange for gold, but the medicine did not help. We decided to go even though the child was still sick in the hopes that we would be able to get medicine for her in Thailand. My niece died in my oldest sister's arms on the first day of our trek into Thailand. We buried her along the path.

The trip took us one day had one night. On the second morning, we walked into the 007 refugee camp at Nang Samet, which is on the border of Thailand and Cambodia.

III

I was 19-years-old in 1979 when my mother, Sok, my oldest sister, Sokhom; her daughter, Somanette; my older sister, Sokhen; her husband, Soklin; her two sons, Kosal and Somanith; and I walked the muddy slippery path out of the jungle into Camp 007 near Nong Samet, Thailand.

The first night we stayed with my niece who had arrived a month earlier; there were 11 other people in the hut. The next day my brother-in-law and my oldest sister led the rest of us in building a simple thatch hut. We couldn't find bamboo so we used small trees and branches to build the frame. We stayed there four months.

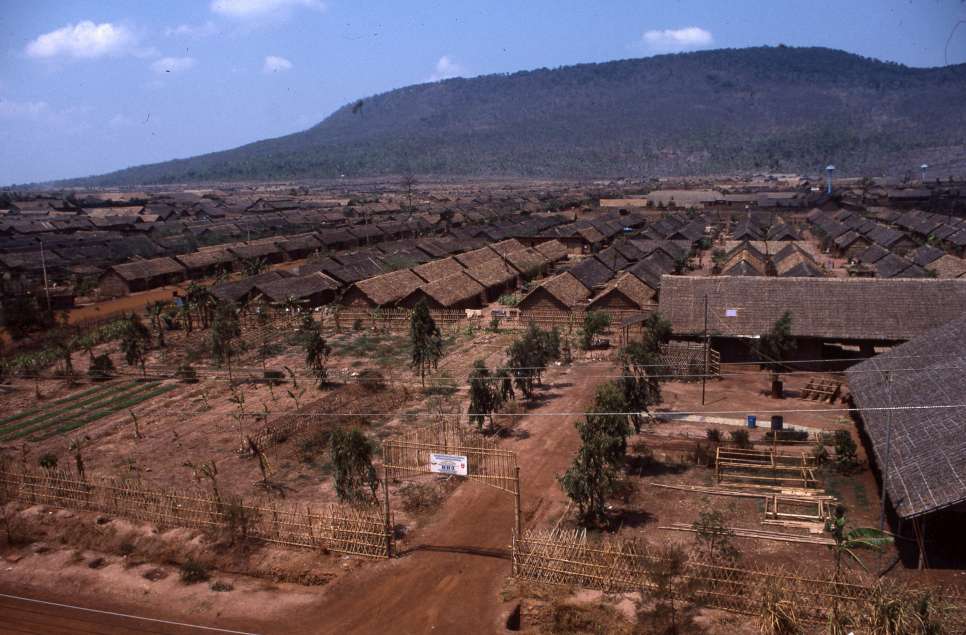

The camp had more than 40,000 people and was totally unplanned: it was a case of thousands and thousands of people fleeing for their lives into a place where they thought they would be safe. Many of them were starving when they came into the camp. All of us depended on humanitarian organizations like the Red Cross, World Vision, Catholic Relief Service, and others.

For us, the important thing was eating. We were so happy to have food again. From the relief organizations we got rice and vegetables; the other food like fish and meat we had to find ourselves.

Every day more people came from Cambodia. Some of the people came into the camp in the hope of staying alive and finding food, while others were not starving at a all and came in the hope of going to a third country.

The camp was managed by the Khmer Serei. Khmer means Cambodia and Serei means freedom or liberation. The Khmer Serei was the name given to separate groups of Cambodia from both the Khmer Rouge and the Vietnamese. They were led by former members of Lon Nol's army. The Khmer Serei leader in Camp 007 was a former colonel in Lon Nol's army.

I got a job in the hospital and then in the information office as a translator. I translated for French, German, Swiss, New Zealand, and American doctors and nurses. My two sisters got jobs in the post office and administration office. We were all paid in rice. Every family was distributed the same ration of rice so that when we combined the rice that we got from our jobs and our ration that was distributed to us we had more than enough: at the end of the month we sold our leftover rice.

I spent my free time studying English and after I had worked a while I had enough money to buy a pair of jeans. It was the first time for me to wear pants since 1975; it felt very good to once again dress the way I wanted to.

We had brought some gold from Cambodia which my brother-in-law used to buy things like clothes, soap, and rice from Thai people which he resold to Cambodians in the camp, and twice he even went back into Cambodia where he sold the things for gold. He would carry the things on his back and once he went as far as Battambang. Many people in the camp smuggled things back into Cambodia.

On January 4, 1980, the Khmer Rouge soldiers attacked the Khmer Serei soldiers inside the camp. I had gone to work in the hospital that day; the hospital was on the other side of the camp from our house. At nine in the morning I heard gunshots; confusion erupted immediately inside and outside of the hospital. One of the nurses, a New Zealand woman, wanted me to get on a bus to go to Khao-I-Dang, a refugee camp about eight kilometers away, but I wanted to go home. I left the hospital and started home, but people coming from the opposite direction told me that others had been killed along the road that led to my home.

I went back to the hospital and decided to try and get to Camp 204 which was about 10 kilometers the opposite direction from Khao-I-Dang. Everyone in the camp was fleeing for their lives with about half of the people going Khao-I-Dang and the other half going to Camp 204.

Someone told me later why the Khmer Rouge had attacked. The Khmer Serei had been black marketing some of the food given to them by the international organizations so the Khmer Rouge were asked to come into the camp to teach the Khmer Serei a lesson. The Khmer Rouge had a camp of their own in the jungle and, even though their camp was not legally sanctioned, they got humanitarian aid. I believe that the humanitarian organizations were interested in saving lives and not in politics. When the Khmer Rouge came into Camp 007 they told the people not to leave, but when the fighting started everyone fled. Khmer Serei soldiers came from Camp 204 to help their fellow soldiers in Camp 007 and the Khmer Rouge soldiers withdrew. As always, innocent people were killed.

By the time I got to Camp 204 it was crowded with people from 007, but I felt safe there. I did not find my family in 204 and thought that they and been some of the "innocent people" killed, so I cried. Shortly after that, however, I met a distant relative of mine who had seen my mother and family just before they had gotten on a bus for Khao-I-Dang. My mother had told him to find me and send me to Khao-I-Dang.

Kao-I-Dang. Picture: UNHCR.That night we believed that the Khmer Rouge would attack the Khmer Serei soldiers in Camp 204 so my distant relative, his girlfriend, and I slept together in a field outside the camp. At midnight we heard shots and saw flashes from guns. The three of us ran into the jungle and kept moving around all night. We were afraid that a stray bullet or shell would hit us. When morning finally came we were in a Thai village. We bought breakfast there and then went back to the camp where I got on a bus for Khao-I-Dang. My distant relative later married his girlfriend; they are still in Thailand.

I met one my sister's friends in Khao-I-Dang and soon found my family. They had left 007 in a hurry, but they had taken most of our belongings with them. Everything that was left behind was lost.

Khao-I-Dang was a legal camp so we had international help. We were told where to build a house and given some plastic sheeting to keep out the rain. Food was distributed to us. At that time there wasn't a water tank in Khao-I-Dang so all the water had to be brought in by bus: we were allowed two buckets of water in the morning and another two at night.

I stayed there one year. I worked in the hospital again, but this time I was paid in money. I got 300 baht or $15 a month, which I used to buy clothes and books.

I met an American man who was a pastor with Youth With a Mission. He worked in the hospital where I translated. He told me about Jesus Christ. He said that Jesus saved us from our sins and he gave me some things to read. I knew him for six months before I thought about becoming a Christian. I had been raised a Buddhist and I thought that I could be both a Christian and a Buddhist. The pastor urged me to accept Christ and I almost did. I used to go to church.

Everyone who worked in the hospital was Christian. I was the only Buddhist there so I thought it best to become a Christian and until I left Khao-I-Dang I told them that I wanted to become a Christian, but I was not baptized. Many young refugees were baptized. My niece was baptized and has a certificate to prove it. I cannot know the hearts of those people who became Christians, but I think that many of them converted because they thought the Christian churches would open the door to a third country for them.

I worked the hospital for the whole year. When I was not working I was trying to teach myself English; a Cambodian man who had been in an English university in Phnom Penh helped me sometimes.

For me it was a happy time. My oldest sister worked in the post office, my other sister gave birth to her third child, we had enough food and we were secure. The only shots I heard were the Thai soldiers shooting Cambodian smugglers. Cambodians were not allowed to go into the Thai village because the Thai government did not want us smuggling things back into the camp. Eventually, they put a big barbed wire fence around the camp to keep us in. One night, two men were killed near the fence outside my home. I heard the shots at night and the next morning I saw their dead bodies. They were shot while trying to get through the fence; they were not willing to obey the rules of the camp. Their families picked up their bodies and buried them.

One of the smugglers not killed was my brother-in-law, Soklin. Because he felt that he desperately needed money, he let the word spread through our friends and relations that he would smuggle people out of Cambodia. Soon a man in America wrote his friend in Khao-I-Dang saying that he would pay $2,000 to anyone who would bring his relations from Phnom Penh. So Soklin, with another man, crawled under the fence and sneaked back into Cambodia. A week later they were in Phnom Penh. They found the people they were looking for and made their way back into Khao-I-Dang. The entire trip took them 15 days. Soklin made the trip twice.

In February of 1980, my oldest sister sent applications to the American and French embassies in Bangkok asking permission for permanent resettlement. We had a relative in France so we thought that perhaps we would be accepted there. She sent in more applications in April, and then in July she sent in an application every week. In September we saw my sister's name on a list posted on the wall of the post office. It would be the United States.

We were elated. We never thought that we would be accepted to the US because we didn't have any family there, but we were and we were told to go to the Panat Nikhom Refugee Camp in Chonburi province.

There days later my mother, my oldest sister, her daughter, and I got on a bus and traveled three and a half hours to Chonburi. We had to leave my married sister, Sokhen, her husband, Soklin, and their three children behind because their names had been placed in separate files from us. They cried and cried.

In the Panat Nikhom camp we lived in a one-room asbestos house with three other families. We were given food, but it wasn't enough. Fortunately, I had saved some money from Khao-I-Dang and my sister still had some gold plus some money from her sister-in-law in Paris, so we could buy all the food we needed.

In the Panat Nikhom camp.Panat Nikhom was very secure. There were two high barbed wire fences around the camp with a patrolled area between the two fences. No unauthorized people got in or out of the camp. On one side of the camp between the two fences was a big market run by the Thai people. For three hours a day we were allowed inside the market and were allowed to buy things — clothes, food, tape players, anything.

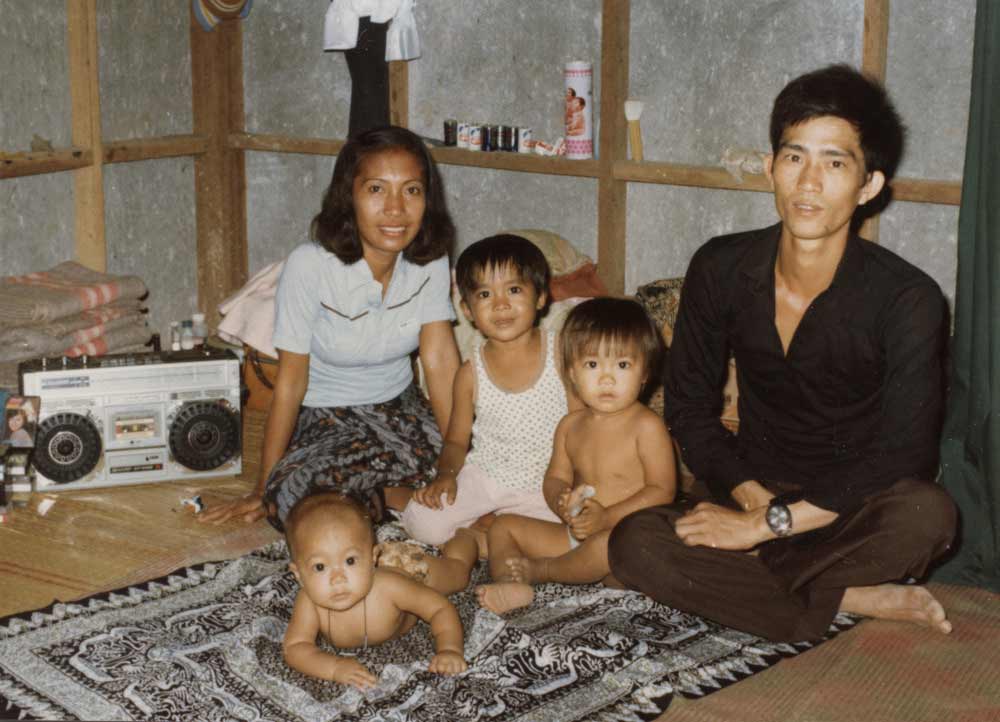

Sokhanno's sister Sokhen, Kosal, Somanit, Kosal, Soklin and, in the front, Somano in the Panat Nikhom refugee camp.I worked as a translator in the office that helped process people for settlement in the United States, the Joint Voluntary Agencies, or JVA. I was there about two months when I saw the initials P.R.P.C. in my file and realized that I was coming here, to the Philippines Refugee Processing Center.

I came to the P.R.P.C. In November 1980. Here we are given enough food — rice, vegetables, fish, and meat. Additionally, we are given English and cultural orientation classes.

Two of Sokanno's cousins, Sokhen (holding a baby), Soklin, and Tom Riddle in the Phipippines Refugee Processing Center.

On March 19 my sister and her family came here and now we are all waiting to go to America, but we don't know where or when.

Sokhanno and a friend posing in their new blue jeans that a camp tailor made for them.

Sokhom and Somanette bathing in a stream near near the Philippines camp.

I read that almost half a million refugees have entered the United States in the last six years. So many people and I will be one of them. When I finally get to America for the first time in six or seven years my life will be in my hands. I'll be 22 in December. I plan to try and keep the promise that I made my father in Phnom Penh about getting a good education. Beyond that, I don't know.

—END—A couple of footnotes:

The man who caught Sokhanno stealing rice eventually became a refugee in Thailand. Sokhanno saw him there, but he refused to speak to her. Sokhanno felt that he was just doing what he felt he had to do to stay alive.

When I met the heroine of Cambodia and the Year of UNTAC in 1992, she had just left Kao-I-Dang where she had lived for 13 years and Sokanno was living in a house with a swimming pool.

home